Introduction

Studying history often involves reading unengaging textbooks, attending monotonous lectures, and memorizing a vast amount of facts, dates, and places that may not seem relevant to students. But is history really boring? No! The subject itself isn’t uninteresting; rather, it’s the way history is taught that makes it feel that way.

“As students learn math, it’s important for them to know that mathematics is more than just numbers and shapes. It’s also about famous mathematicians—the people, personalities, and discoveries that shaped what we know about math today.” [1]

History is not just facts about the past but our interpretation of the past. History helps us understand the present. By examining places, historical events, contexts, and trends, we can gain insights into how they have shaped the world in which we live today. This perspective also applies to the history of mathematics.

Just as the Guard mistakenly implied to King Arthur that coconuts are not migratory, many today erroneously believe that mathematics is either discovered or invented. As Steven Strogatz stated: “Logic leaves us no choice. In that sense, math always involves both invention and discovery: we invent the concepts but discover their consequences. … in mathematics our freedom lies in the questions we ask – and in how we pursue them – but not in the answers awaiting us.” So, let’s take a historical journey to explore how mathematics developed, and “migrated” across the world, starting with the Babylonians.

The Babylonians (ca. 1900 to 1600 BCE)

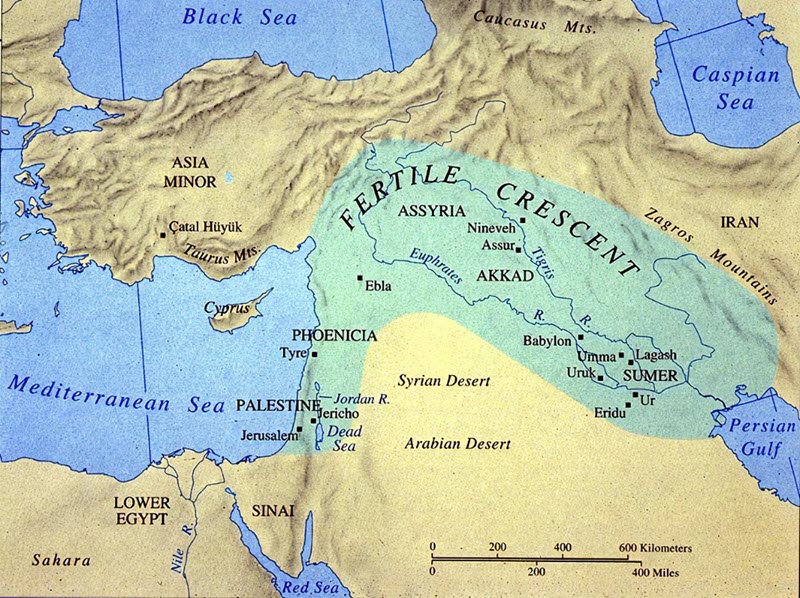

Life in Babylon from 1900 to 1600 BCE was characterized by a mix of culture, governance, and daily life. During this period, a significant change was in the concept and knowledge that the people of Mesopotamia had regarding the world. Traders came to Babylon from as far away as Egypt, where the Middle Kingdom’s splendid days ended. Babylon was the center of a truly international world.

“Under the direction of King Hammurabi, who ruled from around 1792 to 1750 BCE, Babylonia became a force to be reckoned with. He controlled seven city-states in the region, making Babylonia extremely rich and powerful. This provided the stability and resource needed for a mathematical community to develop and thrive. … The Babylonians used mathematics for many practical purposes, including splitting plots of land and calculating tax. Some clay-tablet writers recorded revenues and budgets, and so familiarized themselves with numbers. Unfortunately, they did not sign their names, so we know almost nothing about individual mathematicians from this time. … But some certainly studied mathematics systematically, taking in topics such as algebra and uncovering that famous theorem about triangles often named after Pythagoras (who lived much later).” [2]

Mathematics

The exchange of ideas and knowledge flourished in Babylon, which was located at the crossroads of various civilizations. Sumerian mathematics had a particularly significant influence on Babylonian practices. As a major trade center, Babylon relied heavily on mathematics for various purposes, including accounting, trade calculations, taxation, labor management, and resource allocation.

The Babylonian civilization was primarily agrarian, and the need for effective agricultural practices spurred the development of mathematical tools for land measurement, crop planning, and irrigation management. Additionally, the requirement for accurate calendar systems for both agricultural and religious purposes led to advancements in mathematics, particularly in understanding time-related cycles and calculations.

These practical applications drove progress in both arithmetic and geometry. Furthermore, the establishment of a bureaucracy in Babylon necessitated precise record-keeping, which in turn required mathematical skills. The Babylonian legal system, especially under Hammurabi, utilized mathematics for codifying and enforcing laws, including those related to property and trade regulations.

Key Facts

Significant aspects that contributed to the flourishing of Babylonian mathematics include:

- Base-60 System: The Babylonians used a sexagesimal (base-60) numbering system, which influenced the way they performed calculations and recorded numerical values. This system is believed to have inspired the division of hours and minutes into 60 units that we still use today.

- Clay Tablets: Babylonian mathematicians recorded their mathematical knowledge on clay tablets using cuneiform writing. These tablets contain various mathematical problems, equations, and calculations, providing valuable insights into Babylonian mathematical practices.

- Algebraic Techniques: Babylonian mathematics featured advanced algebraic techniques for solving equations and problems related to geometry and arithmetic. They developed methods for solving quadratic equations and worked with geometric concepts like areas and volumes.

- Astronomical Calculations: Babylonian mathematics was closely linked to astronomy, as the Babylonians were skilled astronomers who made observations of the night sky and developed mathematical models to predict celestial events. Their knowledge of astronomy influenced their mathematical calculations and calendar systems.

Transition

From 1900 BCE to 1600 BCE, mathematics declined, primarily due to political instability, cultural shifts, and the emergence of competing traditions. Although Babylonian mathematics had established a foundation for future developments, this decline marked a transition in the region that ultimately facilitated the rise of other mathematical cultures, such as the Egyptians, who began to develop their mathematical systems.

The Egyptians (ca. 3000 BCE to 332 BCE)

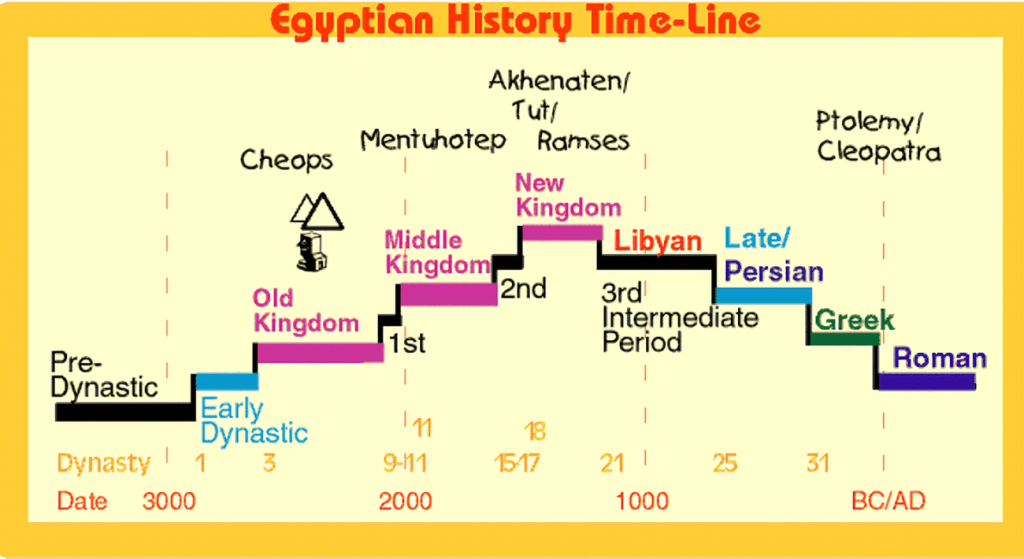

Between 3000 BCE and 332 BCE, Egypt experienced significant political, cultural, and societal developments that shaped its civilization and had a lasting impact on world history. This period included important advancements in politics, culture, religion, and daily life. It encompasses the Early Dynastic, Old Kingdom, Middle Kingdom, and New Kingdom, concluding with the conquest by Alexander the Great.

Egypt was ruled by pharaohs who held absolute power over the state, religion, and military. The political structure of ancient Egypt was highly organized, featuring a bureaucracy that managed various state affairs, including taxation, resource distribution, and public works. The economy was primarily agrarian, relying on the annual flooding of the Nile River, which provided fertile soil for crops such as wheat, barley, and flax. Agriculture was essential not only for sustenance but also for trade. Because of these factors, the Egyptians made significant advancements in mathematics and astronomy, which were crucial for agriculture, religious festivals, and architectural projects. They developed a calendar based on lunar cycles and the annual flooding of the Nile.

Mathematics

The Middle Kingdom (circa 2055–1650 BCE) and the New Kingdom (circa 1550–1070 BCE) were marked by political stability, territorial expansion, and significant cultural achievements. This period also saw a revival in art, literature, and trade. As trade networks developed, Egypt became wealthier and engaged in the exchange of cultural knowledge, including advancements in mathematics. The Egyptians made notable contributions to mathematics, particularly in geometry, arithmetic, and practical applications in everyday life.

“It was the scribes who fostered the development of the mathematical techniques. These government officials were crucial to ensuring the collection and distribution of goods, thus helping to provide the material basis for the pharaohs’ rule. … The majority of problems were concerned with topics involving the administration of the state. … One other area in which mathematics played an important role was architecture. Numerous remains of buildings demonstrate that mathematical techniques were used both in their design and construction. Unfortunately, there are few detailed accounts of exactly how the mathematics was used in building, so we can only speculate about many of the details.” [3]

A significant event occurred during the Late/Persian Period, or Dynasty 27 (525–404 B.C.). “Egypt’s new Persian overlords adopted the traditional title of pharaoh, but unlike the Libyans and Nubians before them, they ruled as foreigners rather than Egyptians. For the first time in its 2,500-year history as a nation, Egypt was no longer independent. … Persian domination actually benefited Egypt under Darius I (521–486 B.C.), who built temples and public works, reformed the legal system, and strengthened the economy.” [4]

Persian rule provided an environment that encouraged the advancement of mathematical knowledge. The Persians brought with them their own knowledge and practices in mathematics, which facilitated the exchange of ideas between Egyptian, Babylonian, and Persian scholars. This cross-pollination enriched the mathematical understanding in Egypt.

The Persians invested in infrastructure, which required mathematical planning and execution, promoting practical mathematics applications in engineering and construction. The Persian administration required efficient record-keeping and tax collection, further developing arithmetic and geometry. This need for precise calculations enhanced mathematical practices.

With the stability provided by Persian rule allowed for a focus on education and scholarship, fostering an environment where mathematics could flourish.

Key Facts

A few notable details about Egyptian mathematics include:

- Hieroglyphic Numerals: The ancient Egyptians used a system of hieroglyphic numerals to represent numbers. These symbols were used for counting, recording quantities, and performing calculations in various contexts, such as trade, construction, and taxation.

- Geometry: Egyptian mathematics excelled in the field of geometry, particularly in the measurement and calculation of land areas, volumes, and shapes. The Egyptians were skilled at surveying and using geometric principles to design and construct buildings, pyramids, and other structures.

- Practical Applications: Egyptian mathematics had a strong emphasis on practical applications and real-world problems. The Egyptians developed methods for calculating areas, volumes, and proportions in construction projects, agricultural planning, and other practical tasks.

- Mathematical Papyri: The ancient Egyptians documented their mathematical knowledge in various mathematical papyri, such as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus and the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus. These texts contain mathematical problems, algorithms, and calculations that offer insights into Egyptian mathematical techniques and practices.

Transition

The Third Intermediate Period (circa 1070–664 BCE) was marked by political fragmentation, with local rulers and foreign powers exercising influence, such as the Libyans and Nubians. This instability contributed to a complex process through which mathematics transitioned from Egypt to Greece. This transition was driven by cultural exchange, intellectual curiosity, and the establishment of academic centers that promoted learning. While the Greeks adopted and adapted Egyptian mathematical practices, they also introduced innovations that transformed the discipline, laying the groundwork for Western mathematics. Ultimately, this knowledge synthesis enriched both cultures and significantly influenced the development of mathematics.

The Greeks (ca. 6 BCE to the 4 CE)

From 6 BCE to 4 CE, Greece underwent a transitional phase marked by significant political, social, and cultural changes. During this time, Greece was under the control of the Roman Republic, which gradually expanded its influence over the region, culminating in the Roman conquest of Greece in the 2nd century BCE. The influences of Hellenism, philosophical thought, and a vibrant religious life continued to shape Greek society, laying the groundwork for future developments in the Roman Empire and beyond.

Mathematics

Mathematics flourished in Greece during this period, as Greek mathematicians built upon the mathematical knowledge of earlier civilizations, such as the Babylonians and Egyptians. This rich heritage provided a strong foundation for further developments in the field. Greek philosophers like Pythagoras and Euclid regarded mathematics as a practical tool for understanding the universe. This philosophical perspective encouraged deeper exploration and abstraction of mathematical concepts.

‘Mathematics, for the ancient Greeks, just as for other cultures, was about more than practical calculations. Many Greek mathematicians believed that mathematics encapsulated a divine form of beauty and was a gateway to understanding the reason for human existence. As Plato wrote in his Republic, “geometry will draw the soul towards truth.” Mathematics was about uncovering “knowledge of the eternal.”’ [2]

The writing of influential texts, such as Euclid’s “Elements,” helped standardize mathematical knowledge and made it accessible to future generations. Wealthy individuals and city-states often supported mathematicians and philosophers, providing them with the necessary resources to pursue their studies and research. Consequently, Greek mathematicians made significant contributions to various areas of mathematics, establishing foundational principles and concepts that continue to influence mathematical thought today.

Key Facts

Key highlights about Greek mathematics include:

- Geometry: Greek mathematicians, such as Euclid and Pythagoras, made remarkable advancements in geometry. Euclid’s Elements is a seminal work that established the foundations of plane geometry and introduced the rigorous deductive method of proof. Pythagoras’ theorem, relating the sides of a right triangle, is one of the most famous results in geometry.

- Number Theory: Greek mathematicians like Euclid and Diophantus delved into number theory, exploring properties of integers and relationships between numbers. Euclid’s Elements includes a book on number theory, while Diophantus is known as the “father of algebra” for his work on solving polynomial equations.

- Mathematical Philosophy: Greek mathematics was closely intertwined with philosophical inquiry, as mathematicians sought to understand the nature of numbers, shapes, and mathematical concepts. Mathematicians like Pythagoras and Plato explored the philosophical underpinnings of mathematics and its relationship to the natural world.

- Applied Mathematics: Greek mathematicians applied their mathematical knowledge to practical problems in areas such as astronomy, engineering, and navigation. Archimedes, for example, made significant contributions to the development of calculus and mechanics, as well as inventing various mathematical tools and machines.

Transition

The decline of Greek mathematics and the subsequent transition to the Islamic Golden Age were influenced by a variety of factors. One significant factor was Greece’s transition to Roman control. This shift redirected focus from Greek intellectual traditions to Roman governance and administration. As a result, there was a decreased interest in Greek scientific and mathematical pursuits. Roman education primarily emphasized rhetoric, law, and governance, rather than mathematics and philosophy, leading to a decline in the study of these subjects. While the Romans appreciated Greek culture, they typically adapted and integrated Greek knowledge instead of expanding upon it, which contributed to a stagnation in mathematical innovation.

As a result of this shift, important centers of mathematical thought, such as the Library of Alexandria and other Hellenistic schools, experienced political instability and eventual decline. This decline led to a loss of scholarly activity and knowledge. The lack of patronage and institutional support for mathematicians and philosophers during the later Roman period further contributed to the decrease in mathematical research and education.

Middle Ages, the Islamic Golden Age (ca. 8 CE to 13 CE)

The Islamic Golden Age refers to a period in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 13th century, during which much of the historically Islamic world was ruled by various caliphates and science, economic development, and cultural works flourished. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign of the Abbasid caliph Harun al-Rashid (786–809) with the inauguration of the House of Wisdom in Baghdad, where scholars from various parts of the world with different cultural backgrounds were mandated to gather and translate all of the world’s classical knowledge into the Arabic language. [5]

The Islamic Empire was vast, encompassing various cultures, languages, and ethnicities. This multicultural environment encouraged interaction and the exchange of ideas. Additionally, the Islamic Empire was situated at the crossroads of major trade routes, facilitating the exchange of goods, ideas, and cultures. These trade networks, extending from Europe to Asia, promoted economic prosperity.

Mathematics

The flourishing of mathematics during the Islamic Golden Age was fueled by a desire to preserve and expand upon earlier knowledge. The Arabs absorbed the scientific achievements of the civilizations they conquered, including those of the ancient Greeks, Romans, Persians, Chinese, Indians, Egyptians, and Phoenicians.

To preserve their knowledge, they established vibrant educational institutions, such as the House of Wisdom and various madrasas, which became centers for mathematical study. These environments encouraged collaboration and the sharing of ideas among scholars. Additionally, wealthy patrons, including caliphs and rulers, supported scholars and funded research, providing the necessary resources for advancements in mathematics.

Scholars did not pursue mathematical knowledge solely for its own sake; they needed precise astronomical calculations for navigation, determining prayer times, and creating calendars. These practical applications were the driving force behind mathematical innovation. To meet these needs, scholars developed advanced techniques in trigonometry and geometry. Additionally, the expansion of trade prompted improvements in arithmetic and accounting. Mathematicians created methods for calculating interest, profit, and currency exchanges, which further advanced the field.

Key Facts

A few notable details about the Islamic Golden Age of mathematics include:

- Translation Movement: One of the defining features of Islamic mathematics was the translation of Greek, Indian, Persian, and Babylonian mathematical texts into Arabic. This translation movement facilitated the assimilation and synthesis of diverse mathematical traditions, leading to the enrichment and expansion of mathematical knowledge in the Islamic world.

- Algebra: Islamic mathematicians, such as Al-Khwarizmi and Al-Kindi, made significant advancements in algebra, introducing algebraic methods and notation that profoundly influenced the development of algebraic thinking. Persian scientist Muhammad ibn Mūsā al-Khwārizmī significantly developed algebra in his landmark text, Kitab al-Jabr wa-l-Muqabala, from which the term “algebra” is derived. The term “algorithm” is derived from the name of the scholar al-Khwarizmi, who was also responsible for introducing the Arabic numerals and Hindu-Arabic numeral system beyond the Indian subcontinent. In calculus, the scholar Alhazen discovered the sum formula for the fourth power, using a method readily generalizable to determine the sum for any integral power. He used this to find the volume of a paraboloid. [WC]

- Trigonometry: Islamic mathematicians excelled in trigonometry, developing trigonometric functions, tables, and methods for solving trigonometric equations. The trigonometric concepts and techniques introduced by scholars like Al-Battani and Al-Biruni contributed to the refinement of trigonometry as a mathematical discipline.

- Mathematical Astronomy: Islamic mathematicians made notable contributions to mathematical astronomy, applying mathematical principles to the study of celestial phenomena and the development of astronomical theories. Scholars like Al-Battani and Al-Biruni conducted precise astronomical observations and calculations that advanced our understanding of the cosmos.

- Preservation and Transmission of Knowledge: Islamic mathematicians played a crucial role in preserving and transmitting mathematical knowledge from ancient civilizations to later generations. The translation and commentary of Greek mathematical texts, combined with original Islamic mathematical works, enriched the mathematical heritage of the Islamic Golden Age and influenced mathematical developments in Europe and beyond.

- Zero: While the birthplace of the numerical zero is debated within history & math circles, India is the most likely. While zero is visible in Mesopotamia, China, & Mayan culture, the numeric value was first assigned in ancient Indian writings. The first known writing that included the numerical zero is found in the Bakhshali Manuscript — a manual to arithmetic for Indian merchants dating as far back as the 7th century AD. Archeologists discovered that this ancient manuscript, written on birch bark, contained black dots under numbers determined to be the first known usage of zero as a numerical value. [6]

Transition

The decline of mathematics during the Islamic Golden Age can be attributed to political instability and fragmentation of power, which led to the rise of smaller states and dynasties. This decentralization often resulted in less support for scholarships and the sciences. With the Islamic world experiencing political fragmentation, certain regions became culturally and intellectually isolated. This isolation hindered the exchange of ideas and collaboration among scholars. Additionally, economic challenges, such as disruptions in trade routes and the decline of significant trading cities, decreased the wealth available for funding scholarly pursuits.

As Islamic society became more conservative, the focus shifted toward religious studies at the expense of secular sciences, including mathematics. The emphasis on theology and jurisprudence reduced interest in mathematical inquiry. The decline in political and economic stability led to decreased patronage for scholars and institutions, diminishing the resources available for research and education in mathematics. Additionally, many learning centers, such as the House of Wisdom, lost their prominence, and fewer institutions were established to continue the tradition of mathematical inquiry.

Two significant factors that influenced the transition in mathematics from the Islamic Golden Age to the Renaissance were the Crusades and the increased interactions between the Islamic world and Europe. In the 12th century, many Arabic mathematical texts were translated into Latin, making the knowledge of Islamic mathematicians accessible to European scholars. Alongside these translations, establishing European universities during the late Middle Ages provided institutional support for studying mathematics and the sciences. These universities became hubs for learning and the exchange of ideas. They began to include mathematics in their curricula, emphasizing the importance of arithmetic, geometry, and algebra in education. The invention of the printing press in the mid-15th century facilitated the widespread dissemination of mathematical texts. This allowed for easier access to new ideas and contributed to the spread of Renaissance mathematics.

What Did We Learn

- The most important fact we learned is that coconuts migrate. “A popular theory suggests that coconuts can travel 110 days or 4,800 km by sea.” [2]

- Like the coconut, we witnessed how mathematics migrated from Babylon to Egypt, Greece, and the Islamic Golden Age.

- We observed how mathematics migrated because of location, what life was like during the period, the impact of the movement of people, goods, and ideas, and how mathematics changed to fit the needs of each period. These factors necessitated the advancement of mathematics from simple arithmetic calculations to form the basis of today’s mathematics.

Renaissance, 18th, 19th, 20th and 21st Century

Part 2 will continue our journey to interpret the past during these periods of mathematics. We will continue examining places, historical events, contexts, and trends to understand how they shaped today’s mathematics.

Supplemental Information

House of Wisdom

The heyday of Islam was marked by the rapid development of Islamic science, culture, and education. This rapid development is supported by the existence of institutions that accommodate these developments. At that time, scientific institutions were established as learning science, culture, and Islamic education. Ibn Killis was a figure and pioneer of the development of education in the Fatimid Caliphate in Egypt. He founded a university and spent thousands of dinars per month to finance it. One of the most important foundations built during the Fatimid period was the construction of Dar al-Hikmah (The house of wisdom) or Dar al-‘Ilm (house of knowledge), founded by al-Hakim in 1005 AD as a waqf-based library, center and spread of extreme Shi’ite teachings. [7]

Pythagorean Theorem

While Pythagoras was an important historical figure in the development of mathematics, he did not figure out the equation most associated with him (a2 + b2 = c2). In fact, there is an ancient Babylonian tablet (by the catchy name of IM 67118) that uses the Pythagorean theorem to solve the length of a diagonal inside a rectangle. The tablet, likely used for teaching, dates from 1770 BCE – centuries before Pythagoras was born in around 570 BCE. [8]

Euclid’s Elements

Euclid’s Elements is a monumental work that holds great significance in mathematics and intellectual thought history. Compiled around 300 BCE by the ancient Greek mathematician Euclid, this treatise is considered one of the most influential mathematical works ever written and has had a lasting impact on the development of geometry and mathematical reasoning.

The key significance of Euclid’s Elements lies in the following aspects:

- Systematic Approach: Elements is structured as a comprehensive compilation of mathematical knowledge, organized into 13 books that cover various aspects of geometry, including plane geometry, solid geometry, number theory, and proportion theory. Euclid’s systematic presentation of geometric principles and theorems laid the groundwork for the deductive method of mathematical proof.

- Deductive Reasoning: Euclid’s Elements introduced the concept of rigorous deductive reasoning in mathematics. Each theorem and proposition in “Elements” is logically derived from previously established results, forming a coherent and interconnected system of geometric knowledge. This emphasis on logical proof and rigorous argumentation set a standard for mathematical rigor that influenced later mathematical practice.

- Euclidean Geometry: Euclid’s work on geometry, particularly the development of Euclidean geometry, has had a profound impact on the study of shapes, angles, lines, and spatial relationships. The geometric axioms and postulates laid out in Elements form the basis of Euclidean geometry, which remains a fundamental branch of mathematics studied to this day.

- Educational Influence: Elements served as a primary textbook on geometry and mathematics for centuries, shaping mathematical education and pedagogy in both ancient and medieval times. The systematic structure of “Elements” and its emphasis on logical reasoning and proof provided a model for teaching mathematics and geometry in educational settings.

Euclid’s Elements stands as a monumental work that exemplifies the power of mathematical reasoning, the elegance of geometric proofs, and the enduring legacy of Euclidean geometry. Its significance lies not only in its mathematical content but also in its influence on the development of mathematical thought and education throughout history.

Translation Movement

The translation movement during the Islamic Golden Age played a pivotal role in the dissemination of knowledge and the enrichment of intellectual scholarship across cultures and civilizations. This movement, which took place from the 8th to the 14th centuries in the Islamic world, involved the translation of scientific, philosophical, and mathematical texts from various ancient civilizations into Arabic, leading to a remarkable cross-cultural exchange of ideas and knowledge.

The significance of the translation movement can be understood through the following aspects:

- Preservation of Knowledge: The translation of Greek, Indian, Persian, and Syriac texts into Arabic helped preserve and safeguard the intellectual heritage of ancient civilizations. By translating works of renowned scholars like Euclid, Aristotle, Ptolemy, and Brahmagupta, Islamic scholars ensured the survival of valuable scientific and mathematical knowledge that might have otherwise been lost.

- Synthesis of Knowledge: The translation movement facilitated the blending and synthesis of diverse intellectual traditions, leading to the cross-fertilization of ideas and the emergence of new insights and discoveries. Islamic scholars integrated Greek, Indian, and Persian mathematical and scientific concepts, enriching their own intellectual heritage and contributing to the development of new disciplines and methodologies.

- Transmission of Knowledge: The translated texts served as a bridge between past and present, allowing Islamic scholars to access and study the works of ancient luminaries in mathematics, astronomy, medicine, philosophy, and other fields. This transmission of knowledge empowered scholars in the Islamic world to build upon the achievements of previous civilizations and make their own original contributions to scholarship.

- Impact on Scholarship: The availability of translated texts broadened the intellectual horizons of Islamic scholars, enabling them to engage with a wide range of ideas and disciplines. The translated works inspired innovations in mathematics, astronomy, medicine, philosophy, and other areas, fostering a culture of intellectual curiosity and innovation that characterized the Islamic Golden Age.

The translation movement of the Islamic Golden Age played a crucial role in preserving, synthesizing, and transmitting knowledge, catalyzing a period of vibrant intellectual exchange and creativity that profoundly influenced the development of mathematics, science, and philosophy in the Islamic world and beyond.

References

[1] Samantha Cleaver, PhD. 2024. “26 Famous Mathematicians Everyone Should Know.” We Are Teachers. https://www.weareteachers.com/famous-mathematicians/.

[2] Kitagawa, Kate and Timothy Revell. The Secret Lives of Numbers: A Hidden History of Math’s Unsung Trailblazers. New York, NY: William Morrow, 2023.

Mathematics shapes almost everything we do. But despite its reputation as the study of fundamental truths, the stories we have been told about it are wrong—warped like the sixteenth-century map that enlarged Europe at the expense of Africa, Asia and the Americas. In The Secret Lives of Numbers, renowned math historian Kate Kitagawa and journalist Timothy Revell make the case that the history of math is infinitely deeper, broader, and richer than the narrative we think we know.

Our story takes us from Hypatia, the first great female mathematician, whose ideas revolutionized geometry and who was killed for them—to Karen Uhlenbeck, the first woman to win the Abel Prize, “math’s Nobel.” Along the way we travel the globe to meet the brilliant Arabic scholars of the “House of Wisdom,” a math temple whose destruction in the Siege of Baghdad in the thirteenth century was a loss arguably on par with that of the Library of Alexandria; Madhava of Sangamagrama, the fourteenth-century Indian genius who uncovered the central tenets of calculus 300 years before Isaac Newton was born; and the Black mathematicians of the Civil Rights era (1954 to 1968), who played a significant role in dismantling early data-based methods of racial discrimination.

Covering thousands of years, six continents, and just about every mathematical discipline, The Secret Lives of Numbers is an immensely compelling narrative history.

[2] “The Mystery of Coconut Migration.” 2023. Asian Inspirations. August 18. https://asianinspirations.com.au/food-knowledge/the-mystery-of-coconut-migration/.

[3] Katz, Victor J. A History of Mathematics: An Introduction. 3rd ed. Boston: Addison-Wesley Longman, 2009.

Provides a world view of mathematics, balancing ancient, early modern and modern history. Problems are taken from their original sources, enabling students to understand how mathematicians in various times and places solved mathematical problems. In this new edition a more global perspective is taken, integrating more non-Western coverage including contributions from Chinese/Indian, and Islamic mathematics and mathematicians.

[4] Allen, James, and Marsha Hill. 1AD. “Egypt in the Late Period (ca. 664–332 B.C.): Essay: The Metropolitan Museum of Art: Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History.” The Met’s Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/lapd/hd_lapd.htm.

[5] McLean, John. 2024. “World Civilization.” The Islamic Golden Age | World Civilization. Accessed September 2. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-hccc-worldcivilization/chapter/the-islamic-golden-age/.

[6] “The Invention Of Zero.” 2020. Setzeus. April 1. https://www.setzeus.com/community-blog-posts/the-invention-of-zero.

[7] Nasution, Abdillah Arif, Aam Slamet Rusydiana, Isfandayani Isfandayani, Eva Misfah Bayuni, Dwi Ratna Kartikawati, and Ihsanul Ihwan. 11/15/2021. “The House of Wisdom as a Library and Center of Knowledge.” DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska – Lincoln. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/libphilprac/6467/.

[8] “Pythagorean Theorem Found On Clay Tablet 1,000 Years Older Than Pythagoras.” 2023. IFLScience. December 22. https://www.iflscience.com/pythagorean-theorem-found-on-clay-tablet-1000-years-older-than-pythagoras-72091.

“Fast, Helpful AI Chat.” 2024. Poe. Assistant. Accessed November 26. https://poe.com/.

I used AI bots in this post to capture ideas that I could not develop on my own without more extensive research. I recall back in the 1990s attending presentations at conferences where the presenter was using crawler bots to gather information for their research. I will continue to use them as needed to present ideas and concepts more clearly to the reader.

This article was inspired by the book The Secret Lives of Numbers: A Hidden History of Math’s Unsung Trailblazers [1], and The Story of Maths and A Brief History of Mathematics by Marcus Du Sautoy. Instead of detailing the specific accomplishments of individual mathematicians, as is often done, this piece focuses on the geographical centers of mathematics and their significance.

Please refer to the Additional Mathematical Migration Information page for more details regarding this post.

Monty Python and the Holy Grail

Guard: Halt! Who goes there?

King Arthur: It is I, Arthur, son of Uther Pendragon, from the castle of Camelot. King of the Britons, defeater of the Saxons, Sovereign of all England!

Guard: Pull the other one!

King Arthur: I am, and this is my trusty servant Patsy. We have ridden the length and breadth of the land in search of knights who will join me in my court at Camelot. I must speak with your lord and master.

Guard: What? Ridden on a horse?

King Arthur: Yes!

Guard: You’re using coconuts!

King Arthur: What?

Guard: You’ve got two empty halves of coconut and you’re bangin’ ’em together!

King Arthur: So? We have ridden since the snows of winter covered this land, through the kingdom of Mercia, through…

Guard: Where’d you get the coconuts?

King Arthur: We found them.

Guard: Found them? In Mercia?! The coconut’s tropical!

King Arthur: What do you mean?

Guard: Well, this is a temperate zone.

King Arthur: The swallow may fly south with the sun or the house martin or the plover may seek warmer climes in winter, yet these are not strangers to our land?

Guard: Are you suggesting that coconuts migrate?

King Arthur: Not at all. They could be carried.

Guard: What? A swallow carrying a coconut?

King Arthur: It could grip it by the husk!

Guard: It’s not a question of where he grips it! It’s a simple question of weight ratios! A five ounce bird could not carry a one pound coconut.

King Arthur: Well, it doesn’t matter. Will you go and tell your master that Arthur from the Court of Camelot is here?

Guard: Listen. In order to maintain air-speed velocity, a swallow needs to beat its wings forty-three times every second, right?

King Arthur: Please!

Guard: Am I right?

King Arthur: I’m not interested!

[A second guard approaches the parapet]

Guard 2: It could be carried by an African swallow!

Guard 1: Oh yeah. An African swallow, maybe — but not a European swallow, that’s my point.

Guard 2: Oh yeah, I agree with that.

King Arthur: [exasperated] Will you ask your master if he wants to join my court at Camelot?!

Guard 1: But, of course, African swallows are non-migratory.

Guard 2: Oh, yeah.

[Arthur begins to depart]

Guard 1: … So they couldn’t bring a coconut back anyway.

~ Monty Python and the Holy Grail

The featured image on this page is from the online article The Mystery of Coconut Migration.