“IF YOU WANT TO BE SUCCESSFUL, FIND SOMEONE WHO HAS ACHIEVED THE RESULTS YOU WANT AND COPY WHAT THEY DO, AND YOU’LL ACHIEVE THE SAME RESULTS.” ~ TONY ROBBINS

In his article, 7 Communication Tips for Data Scientists, Shaw Talebi states, “The following are the communication tips I use most often. Although I’m focusing on technical presentations here, these tips broadly apply to conversations, writing, and beyond.” [1]

Over the years I have learned and used these tips in management, software development, project management, teaching, and training. Mr. Talebi presents them well with reference to data science and general use. However, I am going to focus on the use of these tips in mathematics. Why? Because many people WRONGLY believe mathematics is ONLY about solving equations, memorization and testing. Mathematics is also engaged in proving theorems, formulating and testing conjectures, exploring patterns, and developing new conceptual frameworks. So while equation-solving, memorization and testing are certainly important skill in mathematics, they do not capture the full breadth and depth of this rich and multifaceted field of study.

Tip 1: Use Stories

The narrative structure of stories provides an accessible, relatable framework for people to share and engage with one another. Fostering a culture of storytelling can be a wonderful way to bring people together and deepen mutual understanding. I have often used user stories in software development for the following reason.

“User stories help shift the focus from writing about requirements to talking about them. Every agile user story includes a written sentence or two to describe a product backlog item from a user perspective. And more importantly, each user story sparks future conversations about the functionality the user story represents. Read on to discover more about user stories and the user story template, including user story examples.” [2]

You may be asking how does this apply to mathematics. Stories shift the focus from performing the mechanics of mathematics to talking about mathematics to ensure students understand the concepts underlying their calculations. This implies that students will learn how to do things like construct viable arguments and critique others’ reasoning.

“Another reason that math talk is vital is that educators are called to prepare students for the demands of their future. The lists of 21st century skills that students should master include abilities such as: collaboration and teamwork, critical thinking, problem solving, creativity and leadership. These skills are enhanced much more through promoting math discussions in the classroom, rather than having students take notes and solve problems on their own. Students need practice in speaking and listening, appropriately disagreeing, and explaining their thinking in order to be successful in work and life.” [9]

Tip 2: Use Examples

Using examples in mathematics can be a powerful way to illustrate concepts, demonstrate techniques, and provide a deeper understanding of mathematical ideas. Here are some ways that examples can be valuable in mathematics:

Intuition building: Examples can help build intuition about mathematical objects, relationships, and processes. By working through specific cases, students can develop a better feel for how mathematical ideas behave.

For example, when learning about limits, looking at the limit of a simple function like f(x) = 1/x as x approaches 0 from both sides can give students an intuitive sense of what a limit is and why some limits do not exist.

Exploring patterns and generalizations: Examining a series of examples can reveal patterns, regularities, and structures that suggest more general principles or theorems. This can inspire conjectures and motivate the search for proofs.

For instance, looking at the first few terms of the Fibonacci sequence (0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, …) can lead to observing that each term is the sum of the previous two, suggesting the general formula for the nth Fibonacci number.

Testing and applying concepts: Examples allow students to practice applying mathematical techniques and ideas. Working through examples helps cement understanding and reveals the strengths and limitations of different approaches.

When learning integration techniques like integration by parts, working through examples with various functions can help students master the method and understand when it is applicable.

Counterexamples: Examples can also serve to refute conjectures or disprove proposed generalizations. Finding a single counterexample can be sufficient to show that a statement is false.

For instance, the statement “all quadratic functions have at most two real roots” can be disproven by considering the example f(x) = x2 – 3x + 4, which has no real roots.

Motivating and contextualizing mathematics: Real-world examples can help motivate the study of mathematics by showing how it is applied and its relevance to practical problems.

When introducing the concept of derivatives, examples from physics, engineering, or economics can demonstrate the importance of understanding rates of change.

Examples play a crucial role in mathematics by building intuition, revealing patterns, testing ideas, providing counterexamples, and contextualizing mathematical concepts. The thoughtful use of examples is an essential part of effective mathematics instruction and learning. [3]

Tip 3: Use Analogies

The key is to choose analogies that resonate with the learner’s existing knowledge and experiences. Well-selected analogies act as cognitive bridges, making the unknown knowable and the complex much more straightforward. Incorporating analogies into the learning process can be a highly effective way to enhance comprehension, retention, and the overall learning experience.

Analogies can be very useful in mathematics for helping to explain and understand complex concepts. Here are some ways that analogies are commonly used in mathematics:

- Physical Analogies: Relating mathematical concepts to physical objects or phenomena can make them more intuitive. For example, the concept of a function can be analogized to a machine that takes an input and produces an output. Or the idea of a derivative in calculus can be likened to the rate of change of a position over time.

- Visual Analogies: Representing mathematical ideas geometrically or visually can aid comprehension. For instance, adding fractions can be shown as combining areas of shapes, while multiplication of complex numbers can be depicted as rotations in the complex plane.

- Relational Analogies: Drawing comparisons between the structure or relationships in one mathematical domain and another can reveal underlying connections. An oft-used example is the analogy between the properties of arithmetic operations and those of function composition.

- Metaphorical Analogies: More abstract analogies can lend conceptual understanding, even if the connection is not literal. For example, describing mathematical proofs as “building” a logical argument, or framing the search for solutions as “problem solving”.

The power of analogies in mathematics is that they leverage our intuitive, visual, and relational thinking to scaffold the development of formal, abstract mathematical reasoning. Of course, analogies have limits and shouldn’t be over-extended, but used judiciously they can be invaluable pedagogical and explanatory tools. Effective teachers often rely heavily on insightful analogies to convey mathematical ideas. [3]

Tip 4: Numbered Lists

Numbered lists are commonly used in mathematics to organize and present information, especially in proofs, definitions, and step-by-step solutions. Here are some common ways that numbered lists are used in mathematics:

- Proofs: When presenting a mathematical proof, numbered steps are often used to clearly demonstrate the logical flow of the argument. For example:

- Assume that P is true.

- Applying the theorem on Q, we can conclude that R is true.

- Since R is true, we can deduce that S must also be true.

- Therefore, P implies S, and the proof is complete.

- Definitions: Numbered lists can be used to clearly define mathematical concepts, objects, or properties. For example, a definition of a group might be presented as:

- A group G is a set of elements with a binary operation *.

- The binary operation * is closed, meaning that for all a, b in G, a * b is also in G.

- The operation * is associative, meaning that for all a, b, c in G, (a * b) * c = a * (b * c).

- There exists an identity element e in G such that for all a in G, a * e = e * a = a.

- For each a in G, there exists an inverse element b in G such that a * b = b * a = e.

- Step-by-step solutions: Numbered lists are often used to present the steps of a multi-step solution to a mathematical problem or exercise. This helps the reader follow the logic and understanding the reasoning behind the solution. For example, a solution to a calculus problem might be presented as:

- Take the derivative of the function f(x) with respect to x.

- Evaluate the derivative at the given point x = a.

- Simplify the result and express the final answer.

- Listing properties or characteristics: Numbered lists can be used to enumerate the properties or characteristics of a mathematical object, concept, or structure. For example, a list of the properties of a vector space might include:

- Closure under vector addition

- Closure under scalar multiplication

- Existence of a zero vector

- Existence of additive inverses

- Distributive property of scalar multiplication

Using numbered lists in mathematics helps to organize information, present logical arguments, and guide the reader through step-by-step solutions or definitions. This makes the mathematical content more clear, structured, and easy to follow. [3]

For example, we can use a numbered list to explain the steps needed when graphing quadratic functions with equations in standard form.

To graph f(x) = a(x – h)2 + k

- Determine whether the parabola opens upward or downward. If a > 0, it opens upward. If a < 0, it opens downward.

- Determine the vertex of the parabola. The vertex is (h, k).

- Find any x-intercepts by solving f(x) = 0. The function’s real zeros are the x-intercepts.

- Find the y-intercept by computing f(0).

- Plot the intercepts, the vertex, and additional points as necessary. Connect these points with a smooth curve that is shaped like a or an inverted bowl.

Tip 5: Less is More

Don’t use a big word when a singularly unloquacious and

diminutive linguistic expression will satisfactorily accomplish the contemporary necessity.

Simplicity of words is one of the first principles one should learn. Words do not need to be complicated or difficult in order to make speech effective. In fact, simplicity is a key to understanding and thus a great aid to the memory.

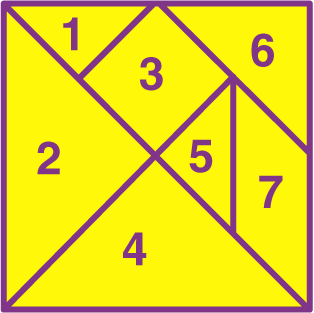

Let’s look at two definitions of the word tangram.

“The tangram is a combination of plane polygonal pieces such that the edges of the polygons are coincident. There are 13 convex tangrams (where a “convex tangram” is a set of tangram pieces arranged into a convex polygon).” – WolframAlpha

“The tangram is an operation puzzle consisting of seven flat polygons, called tans, which are put together to form shapes. The main objective of making tangrams is to replicate a shape by giving only an outline in a puzzle book with the help of all seven pieces without overlap. Alternatively, to generate unique minimalist patterns or designs that are either recognized for their inherent artistic values or as the foundation for challenging others to replicate its outline, we can use the tans.” – BYJU’s

Which is easier to understand? Although the WolframAlpha definition is a more rigorous mathematical definition of tangram (less words), the definition from BYJU’s website (more words) is much simpler and easier to understand. Less is more does not always mean a lesser number of words, but can also mean wording that is less enigmatical.

“Life is really simple, but we insist in making it complicated.” ~ Confucius

Tip 6: Show Don’t Tell

An image is a visual representation of something, such as a photograph or a painting. On the other hand, imagery refers to the use of language to create a mental picture or sensory experience in writing. In other words, imagery is the use of words to create an “image” in the reader’s mind.

Images

Images and media are powerful communication devices. They are useful for conveying concepts and information, and they can help improve comprehension by reinforcing information provided in text. But images and media attract and engage our attention. [6]

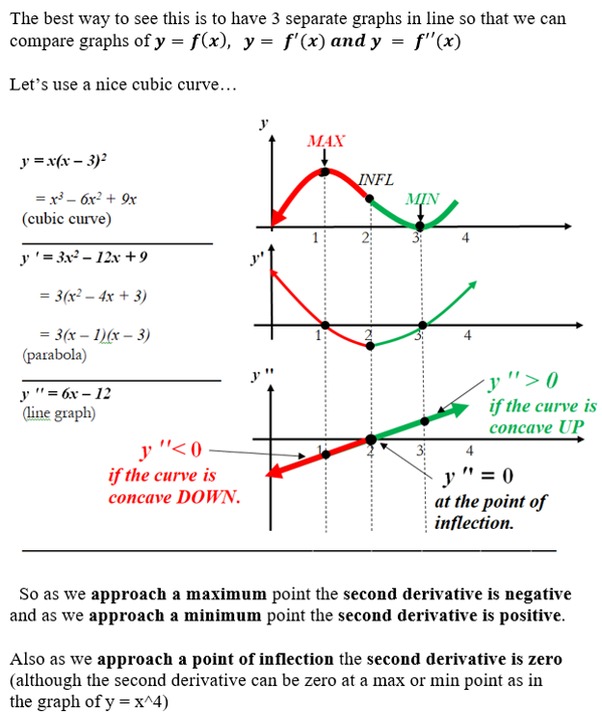

The following is an example from Philip Lloyd who uses wonderful illustrations (e.g., Phantom Graphs) with text to answer mathematical questions.

How does the second derivative test help determine the concavity of a function if the first derivative test already gives us the relative minimum/maximum? [7]

Just read through it and you will see when the curve is concave up or down.

“A mathematician is a maker of patterns, like a painter or poet.” ~ G. H. Hardy

Mathematics is a visual art/science, but all who practice mathematics should also know how to write, and write well.

Writing

“Show, don’t tell” is one of the simplest guidelines in creative writing, and one of the most helpful. In short, it encourages writers to transmit experiences to the reader, rather than just information. [4]

But does one want to transmit experiences to the reader when it comes to mathematics? YES! Mathematics is about communicating ideas and images, and sharing the enthusiasm one has for the subject with others.

“Students rarely think that they are in math classrooms to appreciate the beauty of mathematics, to ask deep questions, to explore the rich set of connections that make up the subject, or even to learn about the applicability of the subject, they think they are in math classrooms to perform.” [9]

Tip 7: Slow Down

In speaking slowly one indicates that he or she has no fear of interruption. People who speak slowly have a higher chance of being heard clearly and understood. They also take up the time of those with whom they’re communicating.

The benefits of speaking slowly include: [5]

- Feeling more relaxed and in control, which is critical when presenting

- Your words have more weight and power because there are fewer of them–you aren’t “devaluing the currency” so to speak

- The audience has an easier time following your presentation because there is less to keep track of and you aren’t overwhelming them with too much information

- You are able to inject more emotion, passion and emphasis into your words because you aren’t rushing to get to the next sentence

- You are able to manage your pacing more effectively, while getting less distracted by random thoughts, side-points and tangents that pop into your head

- You come across as more relaxed, steady, confident and knowledgeable

When communicating mathematical ideas and concepts, you want to speak at a rate to maintain energy and momentum, but slow enough that your key points land effectively in the minds of your listeners.

Conclusion

Not everything can be learned in a classroom, and you cannot learn everything studying one subject. I have learned many different things in my life and applied them in everything I have done. As Tony Robbins says, “copy what they do, and you’ll achieve the same results.” Be a lifelong learner, and remember: “Math is Fun!”

“The first half of my life I went to school,

the second half of my life I got an education.” ~ Mark Twain

References

[1]  Talebi, Shaw. 2024. “The Skill That Holds Back (Most) Data Scientists.” Medium. Towards Data Science. June 14. https://medium.com/towards-data-science/the-skill-that-holds-back-most-data-scientists-a7a7f8744080.

Talebi, Shaw. 2024. “The Skill That Holds Back (Most) Data Scientists.” Medium. Towards Data Science. June 14. https://medium.com/towards-data-science/the-skill-that-holds-back-most-data-scientists-a7a7f8744080.

[2] Cohn, Mike. 2024. “User Stories and User Story Examples by Mike Cohn.” Mountain Goat Software. Accessed June 15. https://www.mountaingoatsoftware.com/agile/user-stories.

[3] “Fast, Helpful AI Chat.” 2024. Poe. Assistant. Accessed June 15. https://poe.com/.

I used AI bots in this article to capture ideas that I could not develop on my own without more extensive research. I recall back in the 1990s attending presentations at conferences where the presenter was using crawler bots to gather information for their research. I am still experimenting with AI bots, and will continue to use them as needed to present ideas and concepts more clearly to the reader.

[4] Glatch, Sean. 2022. “‘Show, Don’t Tell’ in Creative Writing.” writers.com. December 6. https://writers.com/show-dont-tell-writing.

[5] Aquino, Justin. 2022. “Speaking Slowly Will Transform Your Communication.” Cool Communicator. June 17. https://coolcommunicator.com/speaking-slowly-communication/.

[6] “Use Images and Media to Enhance Understanding.” 2024. Digital Accessibility. Accessed June 15. https://accessibility.huit.harvard.edu/use-images-and-media-enhance-understanding.

[7] Lloyd, Philip. 2024. “How does the second derivative test help determine the concavity of a function if the first derivative test already gives us the relative minimum/maximum?” Quora. Accessed June 11. https://qr.ae/psDaXo.

[8] SERC. 2018. “Math Talk: The Value of Discourse in Math Class and Ways to Encourage It.” State Education Resource Center. State Education Resource Center. October 22. https://ctserc.org/component/k2/item/434-math-talk-the-value-of-discourse-in-math-class-and-ways-to-encourage-it.

[9] ⭐ Boaler, Jo, Mathematical Mindsets: Unleashing Students’ Potential through Creative Math, Inspiring Messages and Innovative Teaching, Second Edition. (Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass, 2022).

[10] “What Is the History of Bots?” 2024. Fastly. Accessed June 18. https://www.fastly.com/learning/what-is-the-history-of-bots/.

Medium Member Only

Medium Member Only

⭐ I suggest that you read the entire reference. Other references can be read in their entirety but I leave that up to you.

The featured image on this page is from the under30ceo website.