“The fault, dear Brutus, is not in our stars, But in ourselves, that we are underlings.” – Cassius, a Roman nobleman, talking with his friend Brutus in William Shakespeare’s tragedy, Julius Caesar.

The line “The fault, dear Brutus” begins a longer speech that defines one’s to control their own fate and the influence that ordinary men, like Cesar, should or shouldn’t have in Roman society. Cassius asserts that the “fault “of “underlings” like himself and Brutus is their own. They have allowed themselves to live at the feet of a colossus, Julius Caesar, and unless they do something about it they are going to die meaningless deaths and be forgotten to time. [1]

Jo Boaler is like Cassius. She does not want to live at the feet of a colossus, “narrow mathematics.” She wants you and I to do something about it. (Cassius told Cicero that he has already recruited some of the noblest Romans to undertake “an enterprise.”) In her new book, she presents an “ish” way of changing mathematics to acknowledge the different ways a concept or problem can be viewed, and open the subject to many more students.

Why am I convinced that the “ish” way of mathematics will work? Not only are many of the concepts being successfully used by teachers (even before Jo Boaler wrote this book), and they are concepts I have used over the years to learn new things (e.g., computer programming, art appreciation, and additional mathematics) that I did not study in an institute of learning.

Please read on so I may whet your appetite to read and enjoy Math-ish: Finding Creativity, Diversity, and Meaning in Mathematics.

A New Mathematical Relationship

To fully define the benefits of math-ish, Dr. Boaler describes the current way that mathematics is taught as “narrow mathematics.”

‘Many people are aware of the damages caused by the lack of mathematical diversity in the school system, what I call narrow mathematics. In the world of narrow mathematics, questions have one valued method, and one answer. They are always numerical, and they do not involve visuals, objects, movements, or creativity. Most people have only ever experienced narrow mathematics, which is why we have a country of widespread mathematics failure and anxiety. One example of the damage caused by narrow mathematics comes from the college system. In a noteworthy New York Times article, investigative reporter Christopher Drew shared that every year, students enter four-year colleges intending to major in one of the much-needed STEM subjects of math, science, engineering, and pre-medicine. After the students experience the introductory classes, however-what Drew describes as a “blizzard of calculus, physics and chemistry,” a stunning 60 percent of the students change their majors. Drew quotes David E. Goldberg, an emeritus engineering professor, who describes this as “the math-science death march.”‘ [2]

She concludes this chapter with the topic A NEW MODEL FOR SUCCESS.

“I hope that the ideas in this book help you, and those you work with, achieve beautiful mathematical relationships. Whether you are a parent, a student, an educator, or a person who would simply like to improve your relationship with math, I invite you to meet, or become reacquainted with, two concepts that will come alive in the following pages: mathematical diversity and math-ish. These ideas take place when the diversity provided by different people and ideas combines with a version of mathematics that is open and ish enough to benefit from that diversity.” [2]

The next chapter is where things get really exciting!

Learning to Learn

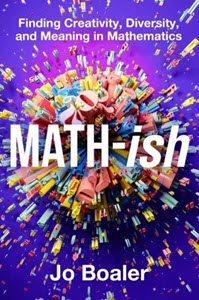

I believe that every student, in every school and in every grade should be taught how to learn. Being able to learn on your own is a skill that will benefit you for the rest of your life. To be a learner, this chapter centers around understanding and applying metacognition. [3]

“I prefer to think of [metacognition] as learning to learn, and learning to be effective in life. Metacognition is a major part of developing into a creative, independent, self-regulating, and flexible problem solver. … In 1979, Stanford professor of psychology John Flavell created the theory of metacognition, and researchers have been investigating its impact ever since then. The word meta comes from the Greek prefix meaning beyond, and metacognition regards the important processes that go beyond thinking, such as planning, tracking, and assessing. Flavell describes metacognition as including knowledge of ourselves, knowledge of the task at hand, and knowledge of strategies, so it is no surprise that it boosts problem-solving, enables mathematical diversity, and enhances work performance.” [2]

I am a lifelong learner, and one thing I have learned is that to accomplishing anything in life involves struggle.

Valuing Struggle

The school where I substitute teach attempts to instill in the students a growth mindset. [4] The students are helped to see that even if the struggle is frustrating in the moment, they should try to reframe the problem as an opportunity for growth and development. With the right mindset, the process of striving to learn is more valuable than the end result.

“Extensive research provides evidence that people who have a growth mindset are more effective in their lives. But what does it mean to have a growth mindset? Many think it means that you know you can learn anything, and that trying is good. Both of these beliefs are important, but I see the defining quality of mindset as a set of beliefs that surround the times when we struggle, make mistakes, and experience hard times in our lives A key feature of a growth mindset, which protects people when things go wrong and helps folks persist through difficult problems, is a changed reaction to times of struggle, and mistakes Neuroscientific studies have shown that whereas people with fixed mindset view mistakes as evidence of their own weakness, people with a growth mindset view mistakes as opportunities to learn.” [2]

Once you see the value in the struggle to learn [7], we move onto the concept of math-ish.

Mathematics in the World

Mathematics is fundamentally built upon the foundational concepts we use in our everyday lives with numbers. The core of mathematics starts with the basic numerical operations – addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division. These are skills we begin developing from a very young age as we learn to count, measure, and make sense of quantities in our daily experiences.

As we progress through math education, the foundations of number sense and numerical operations provide the bedrock for more advanced mathematical concepts and skills, such as:

- Fractions, decimals, and percentages, which build on our basic understanding of parts and wholes.

- Algebra, which generalizes arithmetic into the use of variables and equations.

- Geometry, which connects math to the spatial relationships we observe around us.

- Statistics and probability, which quantify the patterns and uncertainties in our world.

Even the most complex areas of mathematics, like calculus, abstract algebra, or number theory, ultimately trace back to these everyday numerical intuitions we develop from a young age.

By grounding mathematics in this practical, relatable foundation, it becomes a tool we can use to better understand and navigate our lived experiences. The struggle to master the fundamentals of numbers and operations is what gives mathematics its power and applicability across disciplines.

The struggle to build that mathematical foundation from our everyday number sense is critical to developing fluency and facility with higher-level mathematical thinking. It’s a process, but one that pays dividends as we continue to learn and apply these vital skills.

“Numbers are everywhere in the world and we all use them, in some form, every day of our lives. But there is something noteworthy about our everyday use of numbers that differs from the ways we use and learn numbers in school. When we use numbers in our lives and workplaces, they are nearly always imprecise estimates, what I call ish numbers. To some people the idea of ish numbers is heresy, as they believe that numbers have to be accurate, precise, and correct at all times. But ish numbers turn out to be the numbers we most need in our lives, and I believe they could transform people’s approach to mathematics if they were present in their learning journeys.” [2]

But mathematics is more than just numbers. When mathematics is taught, the focus is on formulas, which can make it challenging to see how they relate to real-world situations. Without the ability to connect mathematics to practical applications, some individuals may struggle to find motivation or see the relevance of the subject.

Mathematics as a Visual Experience

By engaging the visual and spatial reasoning faculties, mathematics becomes less abstract and more grounded in our lived experience of the world around us. Struggling to develop this visual-spatial fluency is an important part of becoming mathematically literate.

So you make an excellent point. Mathematics is not just a collection of symbols and formulas – it has a rich visual dimension that is essential to truly grasping and working with mathematical ideas. Embracing the visual nature of math can make the learning process more accessible and rewarding.

“As students are learning about numbers, it is important that they experience them not only visually and physically but also playfully The opposite of this is to experience numbers and operations as a set of remote rules that must be followed. I would like to illustrate the difference with two classroom activities focused on the addition of numbers up to 20-an area of mathematics taught in the US in first grade. One of the activities exemplifies narrow mathematics the other exemplifies mathematical diversity and the development of opportunities that allow students to create mental models.”

Given the information in this chapter, the next logical step is to describe the beauty of what needs to be studied, i.e., not just numbers and formula, but concepts and connections.

The Beauty of Mathematical Concepts and Connections

Mathematics exhibits beauty and elegance in its patterns, symmetries, and structures. Mathematicians often describe the beauty of a mathematical idea or proof, and they appreciate the elegance and simplicity of mathematical concepts. Just like an artist, mathematicians strive to create something aesthetically pleasing and intellectually satisfying. That is why the next excerpt from her book is so marvelous!

“Learning concepts involves thinking deeply, considering, for example, What is a number? How can it be bro- hen apart in different ways to make other numbers? How can it be presented visually? Where do we see numbers in the world? Some students never learn to think conceptually because the teaching they experience is all about rules and methods.” [2]

Math is about more than finding the correct answer. It’s about using concepts, processes and reasoning to apply the best approach for solving a problem. The concepts, processes and reasoning are accumulated over time and start with arithmetic (i.e., numbers and counting, and basic operations), which is the basis for all subsequent mathematics. Once these basic concepts, processes and reasoning are mastered, additional concepts (i.e., geometry, algebra, trigonometry, complex numbers) can be added, and they culminate and are used in calculus. [5]

What Dr. Boaler introduces next is a very important part of learning, if not the most important. Feedback!

Diversity in Practice and Feedback

Feedback loops are essential in maintaining stability, enabling continuous improvement, facilitating learning and adaptation, and ensuring responsiveness and flexibility in various systems and processes. [6] When learning math it is not enough to know that you missed a problem, but why did you miss it, and how can you learn not to repeat the error.

“Deliberate practice is the engagement with meaningful ideas, through which students develop representational models, and it includes a clear feedback loop to provide opportunities for improvement. In a traditional mathematics classroom, students practice content without meaning, diversity, or challenge; they are not encouraged to develop representational models; and the test feedback they receive is a blunt core, with no information on ways to improve. Fortunately, we on do much better, and when we do, students flourish.” [2]

And now the book comes to an end. And what an end as Dr. Boaler sums up math-ish.

A New Mathematical Future

“The examples I have set out in this book so far share different, important qualities of effective teaching, learning, and assessing I started by sharing the importance of students learning how to learn with empowering mathematics strategies and the importance of becoming comfortable with times of struggle. I talked about the value of students learning both precise and “ish” numbers and shapes, and encountering multiple opportunities to develop representational models. I shared the importance of learning mathematics as a set of big ideas and connections, approaching numbers and shapes with flexibility, and, finally, I have shared that when students practice ideas, and get feedback, the ideas and feedback should be diverse and involve applications of mathematics. These different ideas come from many different sources, and one of the goals I have held in writing this book is to combine the advice on education that comes from different fields-education itself, but also psychology, cognitive science, and neuroscience. These different ideas combine into a model of teaching and assessing, represented in figure 8.1.” ( See page 242 in the book for the image.)

Conclusion

Dr. Boaler and I have put our knives in “narrow mathematics.” Et tu, Brute? (And you, esteemed reader?)

References

[1] “The Fault, Dear Brutus.” 2023. Poem Analysis. September 25. https://poemanalysis.com/shakespeare-quotes/the-fault-dear-brutus/.

[2] Boaler, Jo. MATH-ish. 1st ed. HarperCollins Publishers, New York, 2024.

Mathematics is a fundamental part of life, yet every one of us has a unique relationship with learning and understanding the subject. Working with numbers may inspire confidence in our abilities or provoke anxiety and trepidation. Stanford researcher, mathematics education professor, and the leading expert on math learning Dr. Jo Boaler argues that our differences are the key to unlocking our greatest mathematics potential.

In Math-ish, Boaler shares new neuroscientific research on how embracing the concept of “math-ish”—a theory of mathematics as it exists in the real world—changes the way we think about mathematics, data, and ourselves. When we can see the value of diversity among people and multi-faceted approaches to learning math, we are free to truly flourish.

When mathematics is approached more broadly, inclusively, and with a greater sense of wonder and play—when we value the different ways people see, approach, and understand it—we empower ourselves and gain a beneficial understanding of its value in our lives.

[3] “Concept Of Metacognition – John Hurley Flavell.” 2023. Communication Theory. October 23. https://www.communicationtheory.org/concept-of-metacognition-john-hurley-flavell/.

The basis of metacognition appears to imitate the Plan-Do-Check-Act (PDCA) cycle applied to the learning process. The PDCA cycle is an improvement cycle based on the scientific method of proposing a change in a process, implementing the change, measuring the results, and taking appropriate action. It also is known as the Deming Cycle or Deming Wheel after W. Edwards Deming, who introduced the concept in Japan in the 1950s. The steps are:

Plan: Define goals and expectations, and identify opportunities for change

Do: Test the change, such as by conducting a small-scale study

Check: Review the test results, analyze what was learned, and identify any improvements

Act: Take action based on the findings

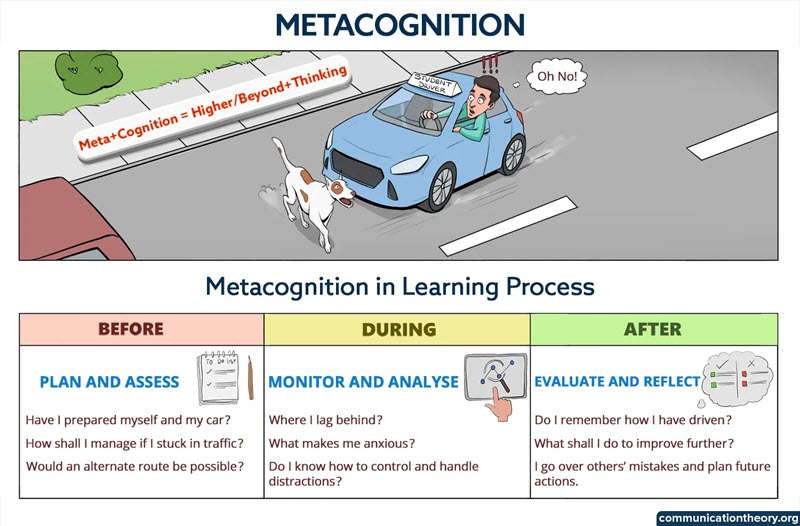

A similar approach is taken in many classes such as English Language Arts (ELA) as shown in the image below. Looks a lot like PDCA. A recipe for success!!

[4] Dweck, Carol S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Robinson, London, UK, 2017.

After decades of research, world-renowned Stanford University psychologist Carol S. Dweck, Ph.D., discovered a simple but groundbreaking idea: the power of mindset. In this brilliant book, she shows how success in school, work, sports, the arts, and almost every area of human endeavor can be dramatically influenced by how we think about our talents and abilities. People with a fixed mindset—those who believe that abilities are fixed—are less likely to flourish than those with a growth mindset—those who believe that abilities can be developed. Mindset reveals how great parents, teachers, managers, and athletes can put this idea to use to foster outstanding accomplishment.

In this edition, Dweck offers new insights into her now famous and broadly embraced concept. She introduces a phenomenon she calls false growth mindset and guides people toward adopting a deeper, truer growth mindset. She also expands the mindset concept beyond the individual, applying it to the cultures of groups and organizations. With the right mindset, you can motivate those you lead, teach, and love—to transform their lives and your own.

[5] Zeke the Geek. 2023. “What Is Mathematics? – Part 2.” Mathematical Mysteries. March 18. https://mathematicalmysteries.org/2023/01/18/what-is-mathematics-part-2/.

[6] Zeke the Geek. 2022. “Ehh, What’s Up, Doc?” Mathematical Mysteries. September 25. https://mathematicalmysteries.org/2022/06/08/ehh-whats-up-doc/.

[7] Cepelewicz, Jordana. 2024. “How Failure Has Made Mathematics Stronger.” Quanta Magazine. May 22. https://www.quantamagazine.org/how-failure-has-made-mathematics-stronger-20240522/.

The topologist Danny Calegari discusses the inevitability of disappointment in math, and how to learn from it. “But there was a good lesson to come out of it, which is, I ended up caring a little bit less what other people think, and am driven much more by curiosity alone. If you want to go into mathematics, doing the mathematics itself has to be the thing that’s the reward, because no one cares, and what’s considered important doesn’t always make sense.”

“Fast, Helpful AI Chat.” 2024. Poe. Assistant. Accessed April 27. https://poe.com/.

I used AI bots in this article to capture ideas that I could not develop on my own without more extensive research. I recall back in the 1990s attending presentations at conferences where the presenter was using crawler bots to gather information for their research. I am still experimenting with AI bots, and will continue to use them as needed to present ideas and concepts more clearly to the reader.