Random facts catch us off guard in the best possible way. They’re unexpected or unusual bits of knowledge that can teach, delight and entertain us. These interesting facts aren’t just amusing pieces of information, they’re legitimately fascinating pieces information that will assist you to uncover the mysteries of mathematics.

”Just the facts, ma’am”

Sgt. Joe Friday, Dragnet

Contents

General

Why do we generally use the letter ‘X’ in an equation instead of another letter?

Because a French guy decided it should be that way, possibly because his printer ran out of letters.

Once, a French man wrote a book, and that French man was René Descartes. Besides Napoleon, he is arguably the most famous French person. He’s responsible for things like modern philosophy and the saying Cogito ergo sum (“I think, therefore I am”).

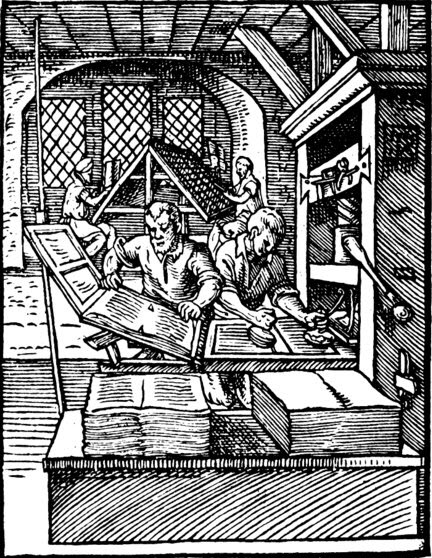

Another thing he’s responsible for – well, several things, really – is one of the greatest contributions to math not made by a Greek person. He needed to tell people about these things, so he wrote some books. He needed to make lots of copies of the books, so he got them printed. (The alternative, and the main method in Europe before Gutenberg invented the printing press, was to write everything out by hand, over and over again.)

In his book La Géométrie, Descartes uses x, y, and z to represent unknown quantities. We’re not completely sure why he did this – it may have just been because those letters come at the end of the alphabet – but according to one theory, it was because his printer had lots of extras of those letters.

Back then, printers weren’t machines; they were people who would take letters out of boxes and arrange them into giant stamps, which could then be used to print things on pieces of paper.

(Interesting side note: The smaller letters, which were used more, were kept in the bottom row of boxes to make them easier for the printer to access, so they were lower case letters. The capital letters, since they were used less, were kept in the top row, so they were upper case. This is where we get those terms from.)

In French, the letters X, Y, and Z are uncommon, so the printers were less likely to run out of them than any other letters (besides K). The theory says that Descartes chose them to represent unknown quantities not only because they come in order at the end of the alphabet, but also due to the printers’ advice.

Whether or not this is true, the first use of X, Y, and Z in this way is found in La Géométrie, a book that tied geometry and algebra together and contributed to the development of calculus.

There are also other theories that suggest it’s an abbreviation of the Greek xenos (“unknown”) or a Spanish abbreviation of the transliteration of the Arabic word al-shalan (see here), but there’s little evidence for either and it’s mostly speculation. The first appearance with evidence is La Géométrie.

Tay, Oscar. “Why do we generally use the letter ‘X’ in an equation instead of another letter? – Quora”. 2023. Quora. https://qr.ae/prulfN.

Were geniuses ever accused of cheating in school?

One of the greatest mathematical minds of all time was once considered a possible cheat. It is not hard to see why.

When Carl Friedrich Gauss was just three (in 1780) he corrected a maths problem his father had gotten wrong.

It was when he was just seven years old though that his genius led to a suspicion that he was a cheat.

The story goes that his teacher decided to have an easy hour-long class, so asked the kids to use their blackboards to determine what the answer would be if you added 1+2+3+4… all the way for all numbers up to +100.

At the end of the lesson most kids had scrawlings all over their blackboards, as the teacher anticipated. You can only imagine that most had the answer incorrect. It is not easy to manually add up so many numbers as a seven year old without making an error.

But when the teacher got to Gauss’ blackboard there was only one number 5,050.

This was the correct answer. And a stunned teacher must have assumed some cheating, but Gauss soon explained how he reached the answer.

Instead of adding up the numbers in order he added them up from the ends. It doesn’t matter after all which order the numbers are added, it should give the same answer.

So he added up 100+1, then 99+2, then 98+3 and as you will notice, if you add up all the pairs, you will have exactly 50 groups of 101 (5,050).

There was only one Gauss, whose genius only grew stronger over time.

Francis, Xanthi. “Were Geniuses Ever Accused Of Cheating In School?”. 2023. Quora. https://qr.ae/prbMJ0.

EXPOUNDED

Let the sum be S = 1 + 2 + 3 + … + (n – 1) + n

Write it backwards S = n + (n – 1) + (n – 2) + … + 2 +1

Add them together 2S = (n + 1) + (n + 1) +(n + 1) + … + (n + 1) + (n + 1)

Therefore 2S = n * (n + 1) (since we have an n amount of (n + 1)’s

Finally, S = ( n * (n + 1) ) / 2

For n = 100, S = ( 100 * 101 )/2 = 5050

When was the first calculator invented?

I will focus on calculators that became popular.

The abacus is very ancient but is more of an assist than a full calculator.

Slide rules do multiplication by adding logarithms on a device resembling a ruler with sliding parts. It also gave you squares and square roots to almost 3 decimal places. This picture shows one similar to the one I used in high school the 1960s. Every engineer and scientist back then owned one and used it regularly. One article described it as “A Computing Device That Put A Man On The Moon”

My sources say that they are around 400 years old:

About 1622, William Oughtred… an Anglican Minister, today recognized as the inventor of the slide rule in its actual form, by placing two such scales side by side and sliding them to read the distance relationships, thus multiplying and dividing directly. He also developed a circular slide rule.

If you are thinking of machine having a keyboard, the Comptometer was patented in 1885. This picture shows a very early model.

The next picture apparently dates to the 1930s.

And this picture shows the innards of a 1964 version. It was powered by electricity. A major advance!

It’s hard for anyone living now to appreciate how revolutionary that invention was. Business accounting requires lots of arithmetic that’s tedious to do by hand. Some branches of science required lots of calculations even then. This picture shows a 1908 ad for this machine.

Calculations were so important that some people made their living as human calculators. Being able to do calculations with the help of a machine was a major advance.

I used a version similar to the one in this picture in the 1960s for my psychological statistics class. Entering successive digits of a long number could be tedious. I don’t miss that machine.

Ten-key calculators were also available by then. I once had a brief job that consisted of entering numbers into the calculator all day long. A few times each day, I got to write down a subtotal.

Ramirez, Israel. “When Was The First Calculator Invented?” 2023. Quora. https://qr.ae/prBrKx.

Historical Math Facts, Information & Timeline

It is believed that Ancient Egyptians used complex mathematics such as algebra, arithmetic and geometry as far back as 3000 BC, such as equations to approximate the area of circles.

Chinese mathematics developed around the 11th century BC and included important concepts related to negative numbers, decimals, algebra and geometry.

Greek mathematics developed from around the 7th century BC, producing many important theories thanks to great mathematicians such as Pythagoras, Euclid and Archimedes.

The Hindu-Arabic numeral system began developing as early as the 1st century with a full system being established around the 9th century, forming the basis of the numerical digits 0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8 and 9 that we use today.

The symbols used for addition (+) and subtraction (-) have been around for thousands of years but it wasn’t until the 16th century that most mathematical symbols were invented. Before this time math equations were written in words, making it very time consuming.

The equals sign (=) was invented in 1557 by a Welsh mathematician named Robert Recorde.

Mathematical developments increased rapidly around the time of the Italian Renaissance in the 16th century and continued through the scientific revolution of the 17th and 18th centuries, becoming increasingly abstract in the 19th and 20th centuries.

“History of Mathematics – Historical Math Facts, Information & Timeline”. 2023. kidsmathgamesonline.com. https://www.kidsmathgamesonline.com/facts/history.html.

The decimal point is 150 years older than historians thought

The decimal point was invented around 150 years earlier than previously thought, according to an analysis of astronomical tables compiled by the Italian merchant and mathematician Giovanni Bianchini in the 1440s. Historians say that this discovery rewrites the origins of one of the most fundamental mathematical conventions, and suggests that Bianchini — whose economic training contrasted starkly with those of his astronomer peers — might have played a more notable part in the history of maths than previously realized.

Marchant, Jo. 2024. “The Decimal Point Is 150 Years Older than Historians Thought.” Nature News. Nature Publishing Group. February 19. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-024-00473-2.

See also Decimal fractional numeration and the decimal point in 15th-century Italy for the article.

Circle

Why Are There 360 Degrees In A Circle, Instead Of Something Useful Like 100?

No need to be obtuse – it’s actually acute story.

Ever wondered why a sudden reversal of opinion is called a “full 180”? Or why a gaming company might call their new product an “Xbox 360” to imply it can offer the full range of entertainment options?

Like everything great in the world, it all comes down to math – specifically, geometry. Both of these throwaway phrases are in fact references to the number of degrees in a single rotation – or to put it in slightly less math-y terms, the number of degrees in a full circle.

A circle split into eight segments of 45 degrees each.

Image credit: IFLScience

But have you ever wondered why, exactly, we decided to split a circle into such a seemingly arbitrary number? In what other situation (outside of “being American”) would somebody decide to make something like 360 the base value for such an important system?

Why are there 360 degrees in a circle?

For the answer to that, we have to go back to the very beginnings of math itself – back before it was even math at all, really. If you want to know who to blame, look no further than the Ancient Babylonians: they were almost certainly the first to split a circle into 360 equal degrees, and it probably happened around 2400 BCE.

So, case closed, right? There are 360 degrees in a circle because that’s what the Ancient Babylonians decided to do some 4,500 years ago, and we just never decided to update it!

Oh, you wanted more of an explanation than that? Well… now we might have a problem.

The truth is that, like so many decisions made multiple millennia in the past, we don’t know for sure what prompted the choice to set 360 as the number of degrees in a circle. But that doesn’t mean we don’t have a few hypotheses, ranging from mathematical ease to geometric beauty to astronomical serendipity.

The astronomical argument

We all come to math via different routes. For the ancient Greeks, it was through geometry, the study of the earth; in India, the subject came with a distinctly more divine flavor.

For the ancient Babylonians, the true purpose of math lay somewhere in the middle: it was a way to figure out the night sky.

“The heavenly phenomena were of great importance to the Babylonians,” wrote Chris Linton, Professor of Applied Mathematics at Loughborough University, in his 2004 book From Eudoxus to Einstein: A History of Mathematical Astronomy.

“They were perceived as omens and just about every possible astronomical event had some significance,” he explained. “For example, when it came to the retrograde motion of the planets it was not simply the retrograde motion itself, but also where it took place with respect to the stars that was important.”

For example, he noted, should Mars leave the constellation Scorpius, your average Babylonian wouldn’t start talking about how you suddenly have an excuse for being more stubborn than usual or something – it was a cosmic sign that you should put your guard up, because bad things were likely to happen.

In a world before the scientific revolution, this kind of, well, magic was really the only control people could wield over their fate. That meant it was important to get it right: to properly figure out the upcoming omens spelled out in the stars, these ancient astronomers would need precision – and luckily, there was a base unit ready and waiting for them to snap up.

“The Babylonians are… responsible for dividing the circle up into 360 equal parts, which we call ‘degrees’,” Linton wrote. “[This] seems to have been due to the length of the year being about 365 days, and so in one day the Sun moves about 1° with respect to the stars.”

In a year, therefore, the sun would have moved a total of about 360 degrees – and in doing so, had returned to its original position. It had, you might say, come full circle.

The divisibility argument

The Babylonians’ obsession with measuring the skies like this resulted in an astronomical sophistication that far outpaced any other contemporary civilization – and quite a few that came after it, too. All the way up to the 16th century, in fact, Western astronomers were using methods of recording planetary movement that were more or less identical to those used by their 3,000-year-old predecessors.

Why? In fact, this was thanks to yet another quirk of Babylonian math: their counting system. Unlike our own, which is decimal or base 10, theirs was sexagesimal – base 60.

Babylonian numerals one through 59.

Image credit: Josell7 via Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

It’s not as arbitrary a choice as it sounds. “The reason for the use of 60 is unclear, but it may well have been because 60 is divisible exactly by lots of small integers, so many calculations can be done without the use of fractions,” Linton explained.

That’s a major benefit in a pre-Zeno mathscape. Compare 60 to 10, for example: you can divide the first equally into three and get a whole number, 20, but not the latter; the same goes for dividing by four and six, neither of which have integer solutions for us, but to the Babylonians were extremely simple to work out.

And if 60 is a useful base for working out divisions, then 360 – that is, 60 multiplied by 6 – is even better. To modern mathematicians, it’s what’s known as a superior highly composite number: with no fewer than 24 divisors, it can be split into two, three, four, five, six, eight, nine, 10, 12, 15, 18, 20, 24, 30, 36, 40, 45, 60, 72, 90, 120, 180 and, of course, 360 itself, without ever leaving a remainder.

It’s an incredibly useful property. Try splitting the world into its 24 time zones using 100 degrees in a revolution – you’ll end up needing to measure out 4.166666… recurring degrees of longitude, which is tedious for a cartographer and impossible for a mathematician. With 360 as your starting point, however, it’s a nice round 15 degrees per time zone (or at least, it would be if people stopped messing with them.)

Of course, this line of thought does raise another question: why multiply by six in particular? Again, this is something we can only really speculate about – but it may have something to do with the Greek geometers who inherited the Babylonian mathematical traditions.

See, if there was one thing the earliest Greek geometers loved, it was triangles. If there were two things they loved, it was triangles and symmetry. Now, if you take a circle and draw two radii coming out from the center, then connect them by a third line equal to the length of that same radius – well, you’ll have drawn yourself an equilateral triangle. Three equal sides; three equal angles; every angle 60 degrees.

An equilateral triangle inscribed inside a circle.

Image credit: Hyacinth via Wikimedia Commons, public domain

Fit six of those triangles together, and they will span the entire circle – making this six-times-60 setup a natural foundation for the entire world of geometry.

An even wackier base unit

Of course, in math things can always be made more complicated, and 360 could only last so long as the number of units in a full rotation before it got swapped out for something even more unwieldy.

Enter the radian – another way of measuring angles, used at least since the 1400s by Islamic mathematicians, but only formalized as a concept in the 18th century. For anything past basic geometry, it’s the radian and not the degree that most scientists will reach for – and for good reason: they are a more natural unit from a mathematical perspective, they produce much more elegant and beautiful formulations of results, and they can simplify some calculations that would otherwise be pretty weird and incomprehensible if using degrees.

But from the outside, radians look even worse than degrees. Why? Because the number of radians in a full circle is… 2π.

That’s right, π – as in, the irrational, transcendental number that’s impossible to write using actual digits. So, next time you’re wondering why you have to work with a number as annoying as 360 to deal with your geometry homework, just remember: it could be worse.

After all – the equilateral triangle probably wouldn’t have caught on so well if we all had to remember its internal angles as 1.0471975511965977461542144610931676280657231331250352736583148641 rad, would it?

Spalding, Katie. “Why Are There 360 Degrees In A Circle, Instead Of Something Useful Like 100?”. 2023. IFLScience. https://www.iflscience.com/why-are-there-360-degrees-in-a-circle-instead-of-something-useful-like-100-68919.

Which one is the greatest mathematician, Gauss or Euler?

Comparing the greatness of mathematicians like Carl Friedrich Gauss and Leonhard Euler is challenging because both made monumental contributions to the field of mathematics. However, examining their achievements and influence can provide some insights into their respective impacts.

Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777-1855)

Contributions

- Number Theory: Gauss’s book “Disquisitiones Arithmeticae” laid the foundations for modern number theory. He proved the Fundamental Theorem of Algebra, which states that every non-constant polynomial equation has a root in the complex numbers.

- Statistics and Probability: He developed the least squares method, a fundamental statistical analysis technique. The Gaussian distribution (normal distribution) is named after him and is central to probability and statistics.

- Geometry and Topology: Gauss contributed to differential geometry, proving the Theorema Egregium, which shows that the curvature of a surface is an intrinsic property. He worked on the theory of geodesics, which is the shortest paths on surfaces.

- Physics: Gauss made significant contributions to electromagnetism, optics, and astronomy. Gauss’s law, a fundamental principle in electromagnetism, describes the distribution of electric charge to the resulting electric field.

Influence and Legacy

Known as the “Prince of Mathematicians,” Gauss’s work is characterized by its depth and rigor. His contributions laid the groundwork for many areas of modern mathematics and physics. Gauss was more selective in his publications, often working on problems extensively before releasing his results.

Leonhard Euler (1707-1783)

Contributions

- Analysis: Euler developed much of modern mathematical analysis, including introducing the concept of a function. He formulated Euler’s identity, e^(iπ) + 1 = 0, which is often cited as an example of mathematical beauty.

- Number Theory: Euler made substantial contributions to number theory, including introducing the totient function and the proof of the infinitude of primes. He also contributed to the development of the theory of partitions.

- Graph Theory: Euler is considered the father of graph theoand his solution to the Seven Bridges of Königsberg problem islem. He introduced the concept of Eulerian paths and circuits.

- Mechanics and Fluid Dynamics: Euler contributed significantly to classical mechanics, including the Euler equations for fluid dynamics and the Euler-Bernoulli beam equation in structural engineering.

- Algebra and Geometry: He worked on the theory of polyhedra and introduced Euler’s formula for polyhedra (V – E + F = 2).

Influence and Legacy

Euler’s prolific output includes more than 800 papers and books covering various mathematical and scientific topics. His ability to work across different areas of mathematics and physics and to solve a wide range of problems is unparalleled. Euler was known for his clear and accessible writing style, making complex topics more understandable.

Conclusion

Both Gauss and Euler were monumental figures in mathematics, each with unique strengths and lasting impacts. Gauss is often celebrated for the depth and precision of his work, while Euler is revered for his prolific contributions and the breadth of his influence across multiple fields. Deciding who is the greatest is subjective and depends on the criteria used for judgment. Both have left indelible marks on the mathematical landscape and continue inspiring today’s mathematicians.

Hans, Devvrat. “Which one is the greatest mathematician, Gauss or Euler?” 2027. Quora. https://qr.ae/p2pmWd.

Calculus

Why is there a dx after f(x) in an integral?

Interestingly, about 50 years ago, some educators decided to drop the dx but the idea was not accepted by many traditional maths enthusiasts.

I will explain where the “dx” actually comes from.

The sum of the areas of these strips gets closer and closer to the actual area under the curve. We can find this limit as follows:

Consider one strip greatly enlarged for clarity.

EDIT. Although the dx does not have any real purpose when performing an integral, it does tell us what to integrate with respect to! And when doing a substitution such as when letting u = sin(x) then du becomes cos(x) dx which certainly does play a part in the rest of the Integration!

“Why is there a dx after f(x) in an integral?” 2023. Quora. https://qr.ae/prbuXo.

Square Root

Why did mathematicians choose a symbol like √ to represent squaring a number? Why didn’t they use SQRT instead of √?

First, they didn’t choose ‘√’ to represent squaring but to represent the square root, whose calculation is the exact opposite operation to squaring.

Second, they wouldn’t use ‘sqrt’ instead of a simple symbol because that would render formulas more complicated.

Still, in many computer languages, ‘sqrt’ is accepted for the square root, to allow its entry from keyboards lacking the √ symbol.

Third, the ‘√’ symbol is very aptly chosen, being a stylized form of the lowercase ‘r’, initial to the latin ‘radix’, the English ‘root’, the French ‘racine’, and even, by coincidence, the Greek ‘ρίζα’ (riza = root).

Mathey, Alexander. “Why did mathematicians choose a symbol like √ to represent squaring a number? Why didn’t they use SQRT instead of √?”. 2023. Quora. https://qr.ae/pys2KR.

Why does √ab not equal √a times √b when a and b are negative?

As long as a and b are positive or zero, it is true that √ab = √a√b, but that’s no longer true when they’re both negative.

For one thing, you can simply show it’s not true. Suppose that they’re both negative. That means they’re negations of positive numbers, a = −c and b = −d where c and d are positive.

To begin with, we know √cd = √c√d. Then √a = √-c = i√c where i is the imaginary number √-1. Likewise, √b = √-d = i√d.

Also, √ab = √(-c)(-d) = √cd. But, √a√b = i√c × i√d = i2√a√b = -√a√b.

Thus, √ab ≠ √a√b when both a and b are negative; instead, they’re negations of each other.

Joyce, David. “Why does √ab not equal √a times √b when a and b are negative?” 2019. Quora. 2019. https://qr.ae/pCWolJ.

Zero

See the Zero webpage.

The featured image on this page is from the pngfind website.