Introduction

I have always been fascinated with dates and time. The concepts of time and how we measure it have intrigued humans for centuries. Some key points about the history and significance of dates and time:

- The measurement of time has evolved significantly, from early calendars based on lunar cycles to the highly precise atomic clocks we use today. Each civilization has developed its own dating systems and calendars.

- The Gregorian calendar, which is the most widely used civil calendar today, was introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582. It standardized the length of the year and the timing of leap years, improving on the earlier Julian calendar.

- Time zones were introduced in the late 19th century as a way to coordinate time across different geographic regions as transportation and communication technologies advanced. This allowed for more efficient scheduling of transportation and communications.

- Accurate timekeeping has become increasingly important for scientific research, telecommunications, navigation, and many other applications in the modern world. Atomic clocks now measure time to an astonishingly precise degree.

- Debates continue around the best ways to define and measure time, such as the merits of a potential “leap second” to account for irregularities in the Earth’s rotation.

- Philosophical questions remain about the nature of time itself – whether it is linear, cyclical, or something else entirely. Theories in physics like relativity have challenged classical notions of time.

The human fascination with time is understandable given its fundamental role in organizing our lives and understanding the world around us. There is still much to explore and discover when it comes to the measurement and experience of time. [8]

Date

Calendars are perhaps one of the most impactful aspects of modern society. There are 3 main types of calendars: solar, lunar, and lunisolar. Around 40 calendars are still in use today, but the main calendars used around the world are the Gregorian, Jewish, Islamic, Hindu, Chinese, Julian, and Persian calendars. [1] Each calendar brings its own unique features and historical context. Cultural shifts, scientific advancements, and societal changes have influenced the adoption and modification of calendars throughout history. [2]

Below are some interesting facts, and some mathematical information, on calendars. More information on calendar mathematics can be found in the Additional Reading section.

Doomsday

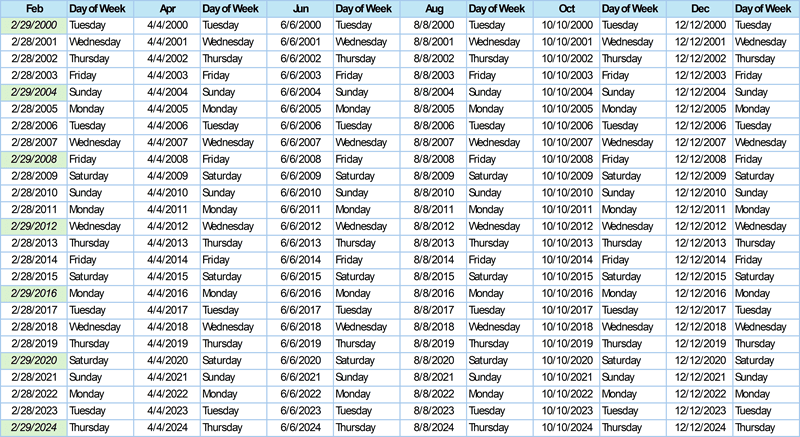

The Doomsday rule, Doomsday algorithm or Doomsday method is an algorithm of determination of the day of the week for a given date. It provides a perpetual calendar because the Gregorian calendar moves in cycles of 400 years. The algorithm for mental calculation was devised by John Conway in 1973, drawing inspiration from Lewis Carroll‘s perpetual calendar algorithm. It takes advantage of each year having a certain day of the week upon which certain easy-to-remember dates, called the doomsdays, fall; for example, the last day of February, 4/4, 6/6, 8/8, 10/10, and 12/12 all occur on the same day of the week in any year. [3]

Gregorian Calendar

The Gregorian calendar is the calendar used in most parts of the world. It went into effect in October 1582 following the papal bull Inter gravissimas issued by Pope Gregory XIII, which introduced it as a modification of, and replacement for, the Julian calendar. The principal change was to space leap years differently so as to make the average calendar year 365.2425 days long, more closely approximating the 365.2422-day ‘tropical’ or ‘solar’ year that is determined by the Earth’s revolution around the Sun. [4]

The Gregorian Calendar is the most widely used calendar in the world today. It is the calendar used in the international standard for Representation of dates and times: ISO 8601:2004.

It is a solar calendar based on a 365-day common year divided into 12 months of irregular lengths. 11 of the months have either 30 or 31 days, while the second month, February, has only 28 days during the common year. However, nearly every four years is a leap year, when one extra—or intercalary—day, is added on 29 February, making the leap year in the Gregorian calendar 366 days long.

The days of the year in the Gregorian calendar are divided into 7-day weeks, and the weeks are numbered 1 to 52 or 53. The international standard is to start the week on Monday. However, several countries, including the US and Canada, count Sunday as the first day of the week. [5]

Julian Calendar

The Julian calendar was proposed by Julius Caesar in 46 BCE as a reform of the earlier Roman calendar. The Roman civic calendar was three months ahead of the solar calendar by the 40s BCE. Advised by the Alexandrian astronomer Sosigenes, Caesar introduced the Egyptian solar calendar, which took the length of the solar year as 365 1/4 days. [6] The Julian calendar became the predominant calendar in the Roman Empire and most of the Western world for over 1,600 years until 1582, when Pope Gregory XIII introduced the Gregorian calendar to correct its drift against the solar year. [7]

The Julian calendar was an early attempt to align the calendar year with the solar year. Here are the key differences between the Julian and Gregorian calendars:

- Leap Year Frequency:

- Julian Calendar: Every 4 years, February 29 is added (leap year).

- Gregorian Calendar: Leap years occur every 4 years, except for years divisible by 100 but not by 400.

- Year Length:

- Julian Calendar: Approximates the solar year as 365.25 days.

- Gregorian Calendar: More accurately approximates the solar year as 365.2425 days.

- Calendar Drift:

- Julian Calendar: Drifts 1 day every 128 years.

- Gregorian Calendar: Drifts only 1 day every 3,323 years.

- Adoption:

- Julian Calendar: Widely used until the 16th century.

- Gregorian Calendar: Introduced by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582 to correct the Julian calendar’s inaccuracies.

The Gregorian calendar provides a more precise alignment with astronomical events, reducing the accumulated error over time. [8]

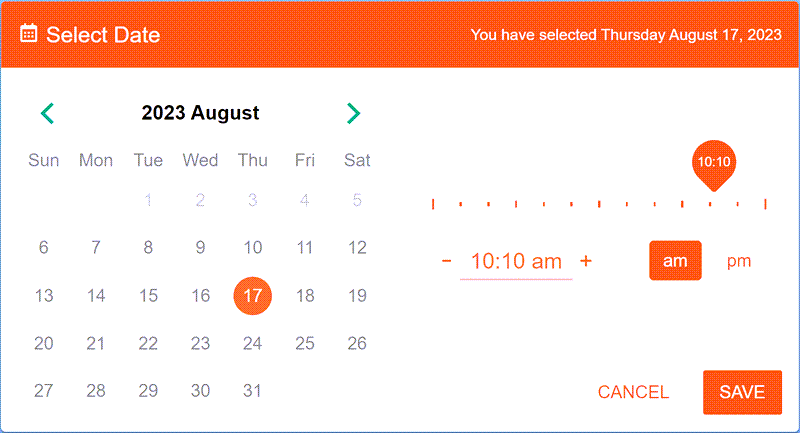

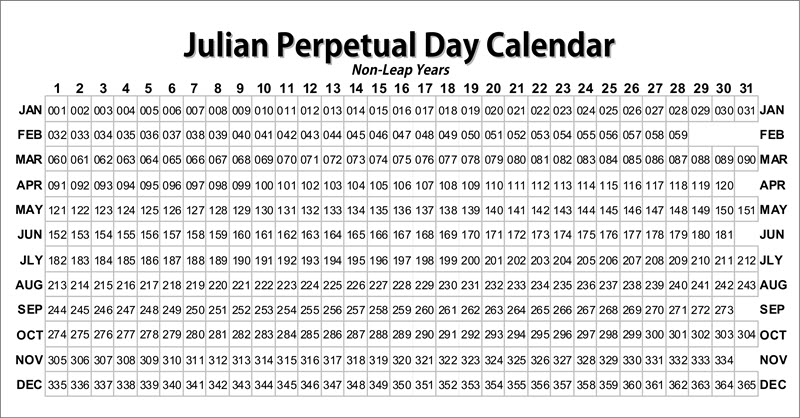

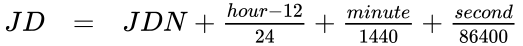

Julian Date

The Julian date (JD) of any instant is the Julian day number plus the fraction of a day since the preceding noon in Universal Time. Julian dates are expressed as a Julian day number with a decimal fraction added. For example, the Julian Date for 00:30:00.0 UT January 1, 2013, is 2456293.520833. This article was loaded at 2024-07-17 01:29:10 (UTC) – expressed as a Julian date this is 2460508.5619213. [9]

The Julian day number (JDN) is the integer assigned to a whole solar day in the Julian day count starting from noon Universal Time, with Julian day number 0 assigned to the day starting at noon on Monday, January 1, 4713 BC, proleptic Julian calendar (November 24, 4714 BC, in the proleptic Gregorian calendar), a date at which three multi-year cycles started (which are: Indiction, Solar, and Lunar cycles) and which preceded any dates in recorded history. For example, the Julian day number for the day starting at 12:00 UT (noon) on January 1, 2000, was 2451545. [9]

Leap Year

Thirty Days Hath September

Thirty days hath September,

April, June, and November,

All the rest have thirty-one,

Except February, twenty-eight days clear,

And twenty-nine in each leap year. [10]

A year is a leap year if the following conditions are satisfied:

- The year is a multiple of 400.

- The year is a multiple of 4 and not a multiple of 100.

// JavaScript function to check if year is a leap year

function checkLeapYear(year) {

if ((year % 4 === 0 && year % 100 !== 0) || year % 400 === 0) {

console.log(year + ' is a leap year');

}

else {

console.log(year + ' is not a leap year');

}

}

const year = prompt('Enter a year:');

checkLeapYear(year);Time

Time is a fundamental concept that refers to the continuous progression of events and the measurement of their duration. It is a fundamental aspect of the physical universe, and its understanding is essential for both scientific and everyday purposes.

Time can be viewed from several perspectives:

- Philosophical perspective: From a philosophical standpoint, time is a complex and often debated concept. Philosophers have grappled with questions such as the nature of time, whether time is an objective property of the universe or a subjective experience, and the relationship between time and causality.

- Scientific perspective: In the scientific realm, time is a key component of the framework used to describe and understand physical phenomena. It is a fundamental dimension in the theory of relativity, where the concept of spacetime unifies space and time into a single continuum. Time is also a crucial factor in various scientific fields, such as physics, astronomy, and geology.

- Practical perspective: In our daily lives, time is a practical tool used for organizing and coordinating activities, measuring the duration of events, and keeping track of schedules and deadlines. The measurement of time has evolved from the use of natural phenomena, such as the movement of celestial bodies, to the development of increasingly accurate clocks and calendars.

The basic units of time measurement include seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, months, and years. These units are based on the rotation of the Earth on its axis, the revolution of the Earth around the Sun, and the phases of the Moon. The precise measurement of time is a crucial aspect of many technological and scientific applications, from the GPS to the synchronization of communication networks.

Understanding and measuring time is essential for our ability to make sense of the world around us, plan and coordinate our activities, and gain deeper insights into the nature of the universe. [8]

Below are some interesting facts, and some mathematical information, on time. More information on time mathematics can be found in the Additional Reading section.

GMT/UTC

Although Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) and Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) [11] share the same current time in practice, there is a basic difference between the two:

- GMT is a time zone officially used in some European and African countries. The time can be displayed using both the 24-hour format (0 – 24) or the 12-hour format (1 – 12 am/pm).

- UTC is not a time zone, but a time standard that is the basis for civil time and time zones worldwide. This means that no country or territory officially uses UTC as a local time.

GMT is the mean (average) solar time at the Greenwich Meridian or Prime Meridian, 0 degrees longitude. The time displayed by the Shepherd Gate Clock at the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, is always GMT. When the sun is at its highest point exactly above the Prime Meridian at the Royal Observatory, it is 12:00 noon at Greenwich. Until 1972, when it was replaced by UTC (universal time coordinated), GMT was also the basis of international civil time standard. It is still used as civil time in UK, when Daylight Saving Time is not in use. [12]

UTC is the 24-hour time standard used as a basis for civil time today. All time zones are defined by their offset from UTC. The offset is expressed as either UTC- or UTC+ and the number of hours and minutes. Primarily, UTC is based on mean solar time at the prime meridian running through Greenwich, UK. For every 15 degrees of longitude east or west, mean solar time changes by 1 hour. Two time components are added together to translate mean solar time to UTC: International Atomic Time (TAI) measured by atomic clocks and Universal Time (UT1), the actual length of a day on Earth. [1]

Unix/Epoch

The Unix epoch, also known as Unix time, POSIX time, or Unix timestamp, is the number of seconds that have elapsed since January 1, 1970 (midnight UTC/GMT), not counting leap seconds12. It is currently defined as the number of non-leap seconds which have passed since 00:00:00 UTC on Thursday, 1 January 1970.

Modular Arithmetic

Calendar systems and date calculations do rely heavily on modular arithmetic, which is a branch of mathematics that deals with the properties of numbers under division.

In the context of calendars and dates, modular arithmetic is used to keep track of the cyclical nature of time, such as the number of days in a week, the number of months in a year, and the number of years in a century.

Here are some examples of how modular arithmetic is used in calendar and date calculations:

- Days of the week: There are 7 days in a week, and the days repeat in a cycle. We can represent this using modular arithmetic, where the day of the week is the remainder when the number of days is divided by 7.

- Months of the year: There are 12 months in a year, and the months repeat in a cycle. We can represent the month of the year using modular arithmetic, where the month is the remainder when the number of months is divided by 12.

- Leap years: The Gregorian calendar has a rule for leap years, where every year divisible by 4 is a leap year, except for years divisible by 100, which are not leap years, unless they are also divisible by 400. This pattern can be expressed using modular arithmetic.

- Date calculations: When calculating the number of days between two dates, we can use modular arithmetic to handle the cyclical nature of the calendar, such as the varying number of days in each month and the leap year cycle.

Modular arithmetic provides a mathematical framework for representing and manipulating these cyclical patterns, allowing for efficient and consistent calendar and date calculations. It’s a fundamental concept that underpins the design and implementation of modern calendar systems, as well as various date-related algorithms and applications. [8]

References

[1] Cobabe, Sarah, Laurie Bradshaw and Sally Odekirk. 2023. “A Guide to the Different Types of Calendars • FamilySearch.” FamilySearch. October 3. https://www.familysearch.org/en/blog/types-of-calendars.

[2] Conversation with Copilot, 7/17/2024

[3] “Doomsday Rule.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. July 11. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doomsday_rule.

[4] “Gregorian Calendar.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. July 13. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregorian_calendar.

[5] “The Gregorian Calendar”. 2024. Time and Date. Accessed July 18. https://www.timeanddate.com/calendar/gregorian-calendar.html.

[6] “Julian Calendar.” 2024. Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. June 28. https://www.britannica.com/science/Julian-calendar.

[7] “Julian Calendar.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. July 13. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_calendar.

[8] “Fast, Helpful AI Chat.” 2024. Poe. Assistant. Accessed June 15. https://poe.com/.

[9] “Julian Day.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. June 21. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_day.

[10] “Thirty Days Hath September.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. June 30. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Thirty_Days_Hath_September.

[11] “Time Zone in UTC, Time Zone (Coordinated Universal Time).” 2024. UTC Time Standard. July 16. https://www.timeanddate.com/time/zone/timezone/utc.

[12] “What is Greenwich Mean Time?” 2024. GMT. Accessed July 16. https://greenwichmeantime.com/what-is-gmt/.

Additional Reading

Date

“A Perpetual Calendar Algorithm”. 2024. homepages.gac.edu. Accessed July 18. https://homepages.gac.edu/~ituba/math303s08/mathideas/mmi10_04ci.pdf,

In this chapter we examined some alternative algorithms for arithmetic computations. Algorithms appear in various places in mathematics and computer science, and in each case give us a specified method of carrying out a procedure that produces a desired result. The algorithm that follows allows us to find the day of the week on which a particular date or will occur.

In applying the algorithm, you will need to know whether a particular year is a leap year. In general, if a year is divisible (evenly) by 4, it is a leap year. However, there are exceptions. Century years, such as 1800 and 19(H), are not leap years, despite the fact that they are divisible by 4. Furthermore, as an exception to the exception, a century year that is divisible by 400 (such as the year 20) is a leap year.

Baker, Matt. 2020. “Mental Math and Calendar Calculations.” Matt Baker’s Math Blog. May 3. https://mattbaker.blog/2020/04/26/mental-math-and-calendar-calculations/.

“Converting Between Julian Dates and Gregorian Calendar Dates”. 2024. USN Astronomical Applications Department. Accessed July 17. https://aa.usno.navy.mil/faq/JD_formula.

“Determination of the Day of the Week.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. June 17. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Determination_of_the_day_of_the_week.

The determination of the day of the week for any date may be performed with a variety of algorithms. In addition, perpetual calendars require no calculation by the user, and are essentially lookup tables. A typical application is to calculate the day of the week on which someone was born or a specific event occurred.

Gent, R.H. van. 2024. Mathematics of the ISO 8601 Calendar – Algorithms. Accessed July 18. https://webspace.science.uu.nl/~gent0113/calendar/isocalendar_text_5.htm.

“Gregorian Calendar.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. July 13. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Gregorian_calendar.

Calendar cycles repeat completely every 400 years, which equals 146,097 days. Of these 400 years, 303 are regular years of 365 days and 97 are leap years of 366 days. A mean calendar year is 365+97/400 days = 365.2425 days, or 365 days, 5 hours, 49 minutes and 12 seconds.

“How to determine the day of the week, given the month, day and year”. 2024. cs.uwaterloo.ca. Accessed July 18. https://cs.uwaterloo.ca/~alopez-o/math-faq/node73.html.

“Julian Date Converter”. 2024. USN Astronomical Applications Department. Accessed July 17. https://aa.usno.navy.mil/data/JulianDate.

“Julian Day Number.” 2024. Calendar Wiki. Fandom, Inc. Accessed July 17. https://calendars.fandom.com/wiki/Julian_day_number.

“Julian Day Numbers.” 2024. Julian Day Calculations (Gregorian Calendar). Accessed July 17. https://quasar.as.utexas.edu/BillInfo/JulianDatesG.html.

“Julian Day.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. June 21. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Julian_day.

Pariona, Amber. 2018. “Calendars Used Around The World.” WorldAtlas. WorldAtlas. March 6. https://www.worldatlas.com/articles/calendars-used-around-the-world.html.

“The Mathematics of the ISO 8601 Calendar”. 2024. webspace.science.uu.nl. Accessed July 17. https://webspace.science.uu.nl/~gent0113/calendar/isocalendar.htm

The purpose of this website is to point out some of the mathematical properties of the week numbering scheme of the ISO 8601 calendar and how to determine the ISO week number of an arbitrary calendar date.

Thormeier, Pascal. 2021. “Algorithm Explained: The Doomsday Rule.” DEV Community. DEV Community. July 21. https://dev.to/thormeier/algorithm-explained-the-doomsday-rule-or-figuring-out-if-november-24th-1763-was-a-tuesday-4lai.

The “Doomsday” of the “Doomsday rule” is not about the end of the world. Every year has so called Doomsdays. A Doomsday is a day whose weekday is known. For every year the Doomsdays have the same weekday.

Time

“Coordinated Universal Time.” 2024. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. July 15. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Coordinated_Universal_Time.

UTC divides time into days, hours, minutes, and seconds. Days are conventionally identified using the Gregorian calendar, but Julian day numbers can also be used. Each day contains 24 hours and each hour contains 60 minutes. The number of seconds in a minute is usually 60, but with an occasional leap second, it may be 61 or 59 instead.[10] Thus, in the UTC time scale, the second and all smaller time units (millisecond, microsecond, etc.) are of constant duration, but the minute and all larger time units (hour, day, week, etc.) are of variable duration. Decisions to introduce a leap second are announced at least six months in advance in “Bulletin C” produced by the International Earth Rotation and Reference Systems Service. The leap seconds cannot be predicted far in advance due to the unpredictable rate of the rotation of Earth.

Nearly all UTC days contain exactly 86,400 SI seconds with exactly 60 seconds in each minute. UTC is within about one second of mean solar time (such as UT1) at 0° longitude, (at the IERS Reference Meridian). The mean solar day is slightly longer than 86,400 SI seconds so occasionally the last minute of a UTC day is adjusted to have 61 seconds. The extra second is called a leap second. It accounts for the grand total of the extra length (about 2 milliseconds each) of all the mean solar days since the previous leap second. The last minute of a UTC day is permitted to contain 59 seconds to cover the remote possibility of the Earth rotating faster, but that has not yet been necessary. The irregular day lengths mean fractional Julian days do not work properly with UTC.

McKay, Dave. 2021. “What Is the Unix Epoch, and How Does Unix Time Work?” How-To Geek. November 10. https://www.howtogeek.com/759337/what-is-the-unix-epoch-and-how-does-unix-time-work/.

Using a single integer to count the number of time steps from a given point in time is an efficient way to store time. You don’t need to store complicated structures of years, months, days, and times. and it is country, locale, and time zone independent.

Multiplying the number in the integer by the size of the time step—in this case, one second—gives you the time since the epoch, and converting from that to locale-specific formats with time-zone adjustments is relatively trivial.

It does give you a built-in upper limit though. Sooner or later you’re going to hit the maximum value you can hold in your chosen variable type. At the time of writing this article, the year 2038 is only 17 years away.

“UTC Time – Coordinated Universal Time – WorldClock.Com – Local Time, Weather, Statistics.” 2024. World Clock. Accessed July 17. https://www.worldclock.com/utc-coordinated-universal-time/.

The plus sign in the +00:00 UTC is known as the offset from Coordinated Universal Time. It tells people by how many hours their time is offset from UTC. For example, the United States is in several time zones: Colorado is in UTC-07:00, while California, Nevada and Oregon are in UTC-08:00. Samoa, in contrast, has a time offset of UTC+13:00; Baker Island and Howland Island, on the other hand, have a negative offset of UTC-12:00.

Once again, time zones aren’t about geographical locations based on their position of North vs South or international country boundaries but rather, the West-East coordination: the same country can have several different time zones, but one time zone may apply to several different countries. To make this easier, think of it this way: if you can draw a vertical line across the map, the countries on that line will share the same time zone. However, if you draw a horizontal line from West to East, the countries on the line will be in different time zones.

Modular Arithmetic

“5.7: Modular Arithmetic.” 2021. Mathematics LibreTexts. Libretexts. July 7. https://math.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Combinatorics_and_Discrete_Mathematics/A_Spiral_Workbook_for_Discrete_Mathematics_(Kwong)/05%3A_Basic_Number_Theory/5.07%3A_Modular_Arithmetic

Modular arithmetic uses only a fixed number of possible results in all its computation. For instance, there are only 12 hours on the face of a clock. If the time now is 7 o’clock, 20 hours later will be 3 o’clock; and we do not say 27 o’clock! This example explains why modular arithmetic is referred to by some as clock arithmetic.

“An Introduction to Modular Arithmetic.” 2024. NRICH. Accessed July 18. https://nrich.maths.org/4350.

The best way to introduce modular arithmetic is to think of the face of a clock.

“Calendar Algorithms”. 2024. sites.millersville.edu. Accessed July 18. https://sites.millersville.edu/bikenaga/number-theory/calendar/calendar.html.

Given a date in history, what day of the week was it?

Gillespie, Maria. 2024. “Days of the Week and Modular Arithmetic.” Mathematical Gemstones. Accessed July 18. https://www.mathematicalgemstones.com/gemstones/amber/days-of-the-week-and-modular-arithmetic/.

Suppose you want to know what day of the week it will be 100 days from today. How would you figure this out? You could look at your calendar and count the days one by one, but that would take a while. A slightly better approach is to use the number of days in each month (“30 days has September…’’) to figure out what the date will be 100 days from today, and then look at your calendar to find that date. But this is also rather cumbersome.

As a better approach, we know that every 7 days, we will be back to the same day of the week. So if you start on a Thursday, after 7 days it will also be Thursday, and after 14 days it will still be Thursday, and so on. The smallest multiple of 7 less than 100 is 98, so 98 days from today, it will be a Thursday. (Yes, I am writing this post on a Thursday.) Therefore, 100 days from today it will be a Saturday.

Kirk, Donna. 2024. “3.7 Clock Arithmetic – Contemporary Mathematics.” OpenStax. OpenStax. Accessed July 18. https://openstax.org/books/contemporary-mathematics/pages/3-7-clock-arithmetic.

When we do arithmetic, numbers can become larger and larger. But when we work with time, specifically with clocks, the numbers cycle back on themselves. It will never be 49 o’clock. Once 12 o’clock is reached, we go back to 1 and repeat the numbers. If it’s 11 AM and someone says, “See you in four hours,” you know that 11 AM plus 4 hours is 3 PM, not 15 AM (ignoring military time for now). Math worked on the clock, where numbers restart after passing 12, is called clock arithmetic.

Clock arithmetic hinges on the number 12. Each cycle of 12 hours returns to the original time (Figure 3.41). Imagine going around the clock one full time. Twelve hours pass, but the time is the same. So, if it is 3:00, 14 hours later and two hours later both read the same on the clock, 5:00. Adding 14 hours and adding 2 hours are identical. As is adding 26 hours. And adding 38 hours.

“Modular Arithmetic.” 2024. Mathematical Mysteries. July 18. https://mathematicalmysteries.org/modular-arithmetic/.

Modular arithmetic is a system of arithmetic for integers, which considers the remainder. In modular arithmetic, numbers “wrap around” upon reaching a given fixed quantity (this given quantity is known as the modulus) to leave a remainder. Modular arithmetic is often tied to prime numbers, for instance, in Wilson’s theorem, Lucas’s theorem, and Hensel’s lemma, and generally appears in fields like cryptography, computer science, and computer algebra.

Pauli, Sebastian. 2024. “MAT 112 Integers and Modern Applications for the Uninitiated.” Clock Arithmetic. Accessed July 18. https://mathstats.uncg.edu/sites/pauli/112/HTML/subsecmodarithmetic.html.

In the following we give applications of the combination of the operation mod and the addition of integers called clock arithmetic.

Recall that the operation mod yields the remainder of integer division. That is, for an integer 𝑎 and a natural number 𝑏 the number 𝑟 = 𝑎 mod 𝑏 is the number such that 𝑎=(𝑞⋅𝑏)+𝑟 for some integer 𝑞 and 𝑟 is a non-negative integer and 𝑟<𝑏.

Applications of the operation mod can be found in arithmetic with hours, days of the week, and months. We start with examples of adding hours and then relate this to using addition and the operation mod.

I used AI bots in this article to capture ideas that I could not develop on my own without more extensive research. I recall back in the 1990s attending presentations at conferences where the presenter was using crawler bots to gather information for their research. I am still experimenting with AI bots, and will continue to use them as needed to present ideas and concepts more clearly to the reader.