Content

- Convenient Numbers (Preferred Numbers)

- Idoneal Numbers (Suitable/Convenient Numbers)

- Summary

- Notes

- Design+Encyclopedia

- References

- Additional Reading

In mathematics, a convenient number can refer to different concepts.

- Simple and easy to use (Convenient Numbers), like 10, 100, or 0.5, because of their simple decimal form.

- Numbers with specific mathematical properties related to sums of squares (Idoneal Numbers), which are integers that have a particular characteristic in representing integers as sums of squares.

Convenient Numbers (Preferred Numbers)

A convenient number is a number that is easy to work with, use, and remember. It’s a number that simplifies calculations or measurements, especially in contexts like design, architecture, or everyday situations. (See Design+Encyclopedia.)

- These numbers are preferred because they are more convenient to measure or verify than values that require interpolation or decimal parts.

- These are numbers chosen for their ease of use in calculations and measurements, particularly in design and engineering.

- The concept is closely related to preferred numbers, which are standardized recommendations for dimensions and values in various applications.

Design and Architecture

Convenient numbers are often whole numbers with few digits or decimal numbers with simple patterns. They’re used to represent measurements, ratios, and proportions, making it easier to design and build things.

Everyday Life

In everyday math or education, “convenient numbers” often refer to numbers that are easy to work with mentally. Dividing a pizza into halves or quarters, or using whole numbers when cooking, are examples of using convenient numbers in daily life, .

- They are often whole numbers, simple decimals, or numbers with easily divisible factors like 1, 2, and 5 (and their powers of 10). For example, 10, 100, 0.5, 25, 50, 1/2, 1/4. These numbers are convenient because they are easily divisible, can be expressed with few digits, or have simple decimal representations, making mental math or calculations easier.

- Numbers representing subdivisions on measuring devices (like a tape measure graduated in intervals of 5) are considered more convenient.

- Round numbers used for estimation or simplification. For example, when estimating 198 + 47, you might round 198 to 200—a more “convenient” number.

These strategies build numerical fluency and reduce reliance on rote memorization.

Finance and Science

In finance, convenient numbers can be used for stock prices or interest rates, while in science, they might represent physical constants.

- Standard resistor values (like 1.5Ω, 10Ω) are convenient for circuit design.

- Metric system values (like 1 cm, 1 m) are convenient for conversions.

- Use 100 to calculate percentages (e.g., 25% of 100 = 25).

- Use 360 to calculate angles and fractions of a circle.

Metric System

During the US’s attempt to adopt the metric system, convenient numbers were proposed as a way to make switching to metric measurements easier.

Go to Landmark Numbers for a short discussion of landmark numbers and the difference between convenient and landmark numbers.

Idoneal Numbers (Suitable/Convenient Numbers)

In number theory, “idoneal numbers,” also known as “convenient numbers,” possess specific properties that relate to the representation of integers as sums or differences of squares. These numbers have intriguing characteristics concerning prime number representation and have been studied by mathematicians such as Euler and Gauss, particularly in the context of identifying large prime numbers. Idoneal numbers are significant in the study of quadratic forms and the distribution of prime numbers.

Definition

– curious_math

The idoneal numbers, also known as Euler’s idoneal numbers, suitable numbers or convenient numbers, are positive integers d such that any integer expressible in only one way as x2 ± dy2 (where x2 is relatively prime to dy2) then n = pk or p = 2pk, where k ≥ 1 and p is a prime. For example, the number 1 is an idoneal number because if x² + 1y² = x² + y² has only one solution with x and y relatively prime, then that solution must be a prime power or twice a prime power.

An equivalent simpler definition is: A positive integer n is idoneal iff it cannot be written as ab + bc + ca for integer a, b, and c with 0 < a < b < c.

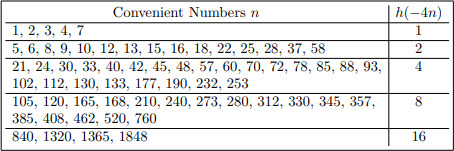

The 65 idoneal numbers found by Gauss and Euler are 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 21, 22, 24, 25, 28, 30, 33, 37, 40, 42, 45, 48, 57, 58, 60, 70, 72, 78, 85, 88, 93, 102, 105, 112, 120, 130, 133, 165, 168, 177, 190, 210, 232, 240, 253, 273, 280, 312, 330, 345, 357, 385, 408, 462, 520, 760, 840, 1320, 1365, and 1848. It is known that if any other idoneal numbers exist, there can be only one more.

History

Euler discovered a method by which he could use certain numbers to find large primes. However, not every number is suitable for this method and hence he gave the name numeri idonei (= suitable, convenient numbers) to those numbers that are suitable. Gauss also considered idoneal numbers from a related but slightly different point of view. After Gauss, many people considered idoneal numbers, often without being aware of the classical connection.

Euler discovered that there are precisely 65 idoneal numbers n ≤ 10,000, the largest being n = 1848. More precisely, he proved (by direct computation):

1 ≤ n ≤ 10,000, then n is idoneal if and only if n is one of he following 65 numbers:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 12, 13, 15, 16, 18, 21, 22, 24, 25, 28, 30, 33, 37, 40, 42, 45, 48, 57, 58, 60, 70, 72, 78, 85, 88, 93, 102, 105, 112, 120, 130, 133, 165, 168, 177, 190, 210, 232, 240, 253, 273, 280, 312, 330, 345, 357, 385, 408, 462, 520, 760, 840, 1320, 1365, and 1848.

In order to convince himself of the validity of this conjecture, Euler stated and proved ten theorems about idoneal numbers. Many of these show that if we impose extra conditions on n, then there are only finitely many such idoneal numbers. These ten theorems are :

- If n is an idoneal number which is a square, then n = 1, 4, 9, 16 or 25.

- If n ≋ 3(mod 4) is idoneal, then 4n is also idoneal.

- If n ≋ 4(mod 8) is idoneal, then so is 4n.

- If λ2n is idoneal, then so is n.

- If n ≋ 2(mod 3) is idoneal, then so is 9n.

- If n ≋ 1(mod 4) is idoneal and n ≠ 1, then 4n is not idoneal.

- If n ≋ 2(mod 4) is idoneal, then so is 4n.

- If n ≋ 8(mod 16) is idoneal, then 4n is not idoneal.

- If n ≋ 16(mod 32) is idoneal, then 4n is not idoneal.

- If n is idoneal and if there is a prime p with p2 < 4n such that n + a2 = p2 , for some a ∈ ℤ, then 4n is not idoneal.

Example Usage

Idoneal numbers, while primarily a concept in number theory, have limited direct applications in everyday life due to their abstract nature. However, they can be indirectly relevant in areas like cryptography, coding theory, or computer algorithms that rely on properties of quadratic forms. Idoneal numbers can be used in optimizing certain computational processes.

Idoneal numbers are linked to quadratic forms like x2 + nxy + y2, which are used in number theory to study unique representations of integers. This uniqueness property can be applied in cryptography, where generating unique keys or identifiers is crucial. For simplicity, let’s focus on an idoneal number like n=1 and its quadratic form x2 + xy + y2.

Suppose a small-scale secure messaging app needs to generate unique numerical identifiers for user authentication tokens. These identifiers must be derived in a way that ensures they are unique and difficult to forge, and the system uses a quadratic form based on an idoneal number to achieve this.

- The app uses the quadratic form x2 + xy + y2 (where n=1, an idoneal number) to generate token identifiers.

- For each user, the system selects a pair of integers (x,y) with gcd(x,y) = 1 and computes the identifier.

- Let’s say for user Alice, the system picks x = 1, and y = 2:

12 + 1⋅2 + 22 = 1 + 2 + 4 = 7

So, Alice’s token identifier is 7. - For user Bob, the system picks x = 2, and y = 3:

22 + 2⋅3 + 32 = 4 + 6 + 9 = 19

Bob’s token identifier is 19.

- Let’s say for user Alice, the system picks x = 1, and y = 2:

- The property of idoneal numbers ensures that numbers like 7 or 19, when generated by this form with gcd(x,y) = 1, have a unique representation (up to sign or order). This uniqueness reduces the chance of two users accidentally receiving the same identifier, which is critical for security.

- The app uses these identifiers as part of a larger cryptographic key or as a seed for generating secure session tokens, ensuring each user has a distinct and verifiable token.

Summary

It is essential to identify the different meanings based on the context in which they are used.

- The first definition (Convenient Number) focuses on practical utility for everyday tasks, especially in measurement and design, and is influenced by the base-10 number system and how physical quantities are interacted with.

- The second definition (Euler’s Idoneal Numbers) is a specialized concept in number theory, related to the properties of quadratic forms and prime numbers.

Notes

Benchmarks

In mathematics, benchmarks are specific, readily understandable numbers or fractions used as reference points to estimate, compare, or order other numbers or fractions. They act as anchors, making it easier to grasp the relative size and position of less familiar values.

- Benchmark Numbers: These are typically multiples of 10 or 100, like 10, 25, 50, 100, etc.

- Benchmark Fractions: Common fractions like 1/4, 1/2, and 3/4 are used to compare other fractions.

- Other Benchmarks: In some contexts, other familiar quantities or measurements can serve as benchmarks. For example, knowing the size of a standard sheet of paper can help estimate the size of other rectangular objects.

Breaking Apart Numbers

Breaking apart numbers, also known as decomposing or partitioning, involves separating a number into its component parts based on place value or other factors to simplify calculations or understand the number’s structure. This strategy is particularly useful for addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division, making larger numbers easier to manage mentally.

Addition

- Breaking down numbers by place value: Instead of adding 35 + 27 directly, you can break them into tens and ones (30 + 5 and 20 + 7). Then, add the tens (30 + 20 = 50) and the ones (5 + 7 = 12) separately, and finally combine the results (50 + 12 = 62).

- Making friendly numbers: You can adjust one addend to make a ten (e.g., in 38 + 6, break the 6 into 2 and 4, add the 2 to 38 to make 40, then add the remaining 4).

- Using a number line: Visually represent the numbers on a number line and break the second addend to make jumps to friendly numbers.

Subtraction

- Breaking down the subtrahend: You can break the number you’re subtracting (the subtrahend) into tens and ones to make the subtraction process easier. For example, in 45 – 18, break 18 into 10 and 8. Then, subtract 10 from 45, and then subtract 8 from the result.

- Borrowing from the next place value: If you need to subtract a larger digit from a smaller digit in the ones place, break down the larger number into tens and ones to “borrow” from the tens place.

Multiplication

Distributive Property: Break down one of the numbers into its tens and ones and then multiply each part by the other number separately. For example, to calculate 7 x 43, you can break 43 into 40 and 3. Then, multiply 7 by 40 (7 x 40 = 280) and 7 by 3 (7 x 3 = 21), and finally add the results (280 + 21 = 301).

Division

Partial Quotients: Break the dividend into smaller, more manageable numbers that are easier to divide.

Compatible Division

Compatible numbers in math are numbers that are easy to perform calculations with mentally, especially in division. They are used to estimate quotients by finding numbers close to the original dividend and divisor that are easily divisible. This helps in quickly approximating the result of a division problem without needing precise calculations.

- Identify the dividend and divisor: In a division problem like 2692 ÷ 28, 2692 is the dividend and 28 is the divisor.

- Round the divisor to a multiple of 10: For 28, a compatible number would be 30.

- Round the dividend to the nearest multiple of the new divisor: 2692 can be rounded to 2700, as it’s the closest multiple of 30.

- Divide the compatible numbers: 2700 ÷ 30 = 90. This gives an estimated quotient.

If and Only If

“If and only if” is a biconditional logical connective between statements. It is shortened as “iff”. To say “A only if B” means that A can only be true when B is true, meaning B is necessary for A to be true. To say “A if and only if B” means that A is true if B is true, and B is true if A is true, which means A is both necessary and sufficient for B.

Partial Quotients

Partial quotients is a method for dividing numbers, especially large ones, by breaking the division into smaller, more manageable steps. It involves estimating how many times the divisor goes into the dividend, subtracting that multiple, and repeating the process until you reach a remainder smaller than the divisor. The sum of all the estimated quotients (partial quotients) is the final answer.

Let’s divide 654 by 3 using partial quotients.

218 <-- Partial Quotients (sum of these is the final quotient)

----

3 | 654

-600 (200 x 3)

----

54

-30 (10 x 3)

----

24

-24 (8 x 3)

----

0- Set up: Write the dividend (654) inside the division bracket and the divisor (3) outside.

- Estimate and subtract: Think about multiples of 3 that fit into 654. 100 x 3 = 300, which is too small. 200 x 3 = 600, which is closer. Subtract 600 from 654, leaving 54.

- Continue: How many times does 3 go into 54? It goes in 10 times (10 x 3 = 30). Subtract 30 from 54, leaving 24.

- Final step: 3 goes into 24 eight times (8 x 3 = 24). Subtract 24, leaving 0.

- Add the partial quotients: Add the numbers you multiplied by 3: 200 + 10 + 8 = 218.

- Result: 654 divided by 3 is 218.

Preferred Numbers

Preferred numbers, also known as preferred values, are a system of standardized sizes and dimensions used in engineering and manufacturing. They help reduce the variety of sizes needed while ensuring compatibility. Based on geometric series, each number is a fixed percentage larger than the one before it. This standardization lowers production costs and makes logistics easier.

Rounding and Compensating

Rounding and compensating is a mental math strategy used to simplify calculations by adjusting numbers to make them easier to work with, then adjusting the result to account for the initial change. This technique is particularly useful for addition and subtraction problems.

Up to Sign or Order

When something is said to be “unique up to sign or order”, it means that while there might be multiple ways to express or represent a mathematical object, these different representations are considered the same if they only differ in their sign or the order of their elements.

- Up to Sign: This means that if two objects differ only by their positive or negative sign, they are considered equivalent.

- Example: The numbers 4 and -4 are considered equal up to sign. You can obtain one from the other by just changing the sign.

- Up to Order: This signifies that the sequence or arrangement of elements within an object doesn’t affect its fundamental identity.

- Example: The prime factorization of 12 is unique up to order. While you can write it as 2 x 2 x 3 or 3 x 2 x 2, these are considered the same factorization because the primes themselves are the same, just in a different sequence.

Design+Encyclopedia

“A convenient number is a numerical value that is easy to remember and use. These numbers are often used in design and architecture to enable designers to refer to specific measurements and ratios without having to calculate them. They are typically whole numbers with few digits or decimal numbers with a simple pattern. Common convenient numbers are frequently based on the Fibonacci series, which is a sequence of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers. Fibonacci numbers are often used to design aesthetically pleasing proportions in architecture, such as the golden ratio. In addition to design and architecture, convenient numbers are also used in various other fields such as finance and science. For example, in finance, convenient numbers are often used to represent stock prices or interest rates. In science, convenient numbers are used to represent physical constants or other important values. Convenient numbers can also be used in everyday life. For example, when dividing a pizza among friends, it is convenient to divide it into equal parts, such as halves or quarters. Similarly, when measuring ingredients for a recipe, it is convenient to use whole numbers or fractions that are easy to remember and measure. Overall, convenient numbers are important in various fields and aspects of everyday life. They make it easier to remember and use numerical values, and can help to create aesthetically pleasing designs or achieve balance and harmony in various contexts.” — Michael Martinez

“In design, a convenient number is any number that is easy to remember and replicate. It is typically used when dimensions need to be matched, for example in the creation of a pattern or to achieve an aesthetic balance. Convenient numbers often come in the form of ratios or multiples of another number. A common example is the use of the golden ratio in design, which is the ratio of 1:1.618. This ratio of 1:1.618 is often used in design to create visual balance and harmony. Other convenient numbers often used in design include whole numbers such as 5, 10, or 15, and fractions such as 1/4, 1/2 and 3/4.”

— Ji-Soo Park

“Convenient Numbers are numerical values that are easy to remember and use because they are whole numbers, generally with few digits, or decimal numbers with a simple pattern. These numbers are used frequently in design and architecture, enabling designers to easily refer to specific measurements and ratios without having to calculate them. Common Convenient Numbers are frequently based on the Fibonacci series, which is a sequence of numbers where each number is the sum of the two preceding numbers. Fibonacci numbers are often used to design aesthetically pleasing proportions in architecture, such as the golden ratio.” — Lauren Moore

References

“29.1: Using the Partial Quotients Method.” 2022. Mathematics LibreTexts. Libretexts. March 27. https://math.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Arithmetic_and_Basic_Math/Basic_Math_(Grade_6)/05%3A_Arithmetic_in_Base_Ten/29%3A_Dividing_Decimals/29.01%3A_Using_the_Partial_Quotients_Method.

“Convenient Number.” 2025. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. March 25. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Convenient_number.

“Convenient Number.” 2025. Wikiwand. Accessed August 11. https://www.wikiwand.com/en/articles/Convenient_number.

“Equivalence Relation – Definition, Proof, Properties, Examples.” 2025. CUEMATH. Accessed August 12. https://www.cuemath.com/algebra/equivalence-relations/.

“Euler’s Idoneal Numbers (Also Called Suitable Numbers or Convenient Numbers).” 2025. Instagram. curious_math. Accessed August 11. https://www.instagram.com/p/CNxFxHUjbqn/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link.

“Euler’s “numerus idoneus” (or “numeri idonei”, or idoneal, or suitable, or convenient numbers).” 2025. THE ON-LINE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF INTEGER SEQUENCES®. Accessed August 11. https://oeis.org/A000926.

Hagedorn, Thomas R. “PRIMES OF THE FORM x2 + ny2 AND THE GEOMETRY OF (CONVENIENT) NUMBERS” 2025. The College of New Jersey. Accessed August 11. https://hagedorn.pages.tcnj.edu/files/2022/08/Geometry-of-Convenient-Numbers.pdf.

“Idoneal Number.” 2025. From Wolfram MathWorld. Accessed August 11. https://mathworld.wolfram.com/IdonealNumber.html.

“Idoneal Number.” 2025. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. April 3. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Idoneal_number.

“Idoneal Numbers.” 2025. GeeksforGeeks. GeeksforGeeks. July 15. https://www.geeksforgeeks.org/dsa/idoneal-numbers/.

“Idoneal Numbers.” 2025. Numbers Aplenty. Accessed August 11. https://www.numbersaplenty.com/set/idoneal_number/.

Kani, Ernst, “Idoneal Numbers and some Generalizations.” 2025. Queens University. Department of Mathematics and Statistics. Accessed August 11. https://mast.queensu.ca/~kani/papers/idoneal-f.pdf.

Milton, Hans J. “The Selection of Preferred Metric Values for Design and Construction.” 1978. GovInfo. NBS Technical Note 990. https://www.govinfo.gov/app/details/GOVPUB-C13-f5fea679df4c3a1c2e3e1dd63488707c.

Moore, Lauren. 2025. “Convenient Number.” Design+Encyclopedia. A’ Design Award & Competition SRL. August 11. https://design-encyclopedia.com/?T=Convenient+Number.

“Primary Decomposition.” 2025. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. August 11. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Primary_decomposition.

“preferred numbers.” 2025. Sizes. Accessed August 12. https://www.sizes.com/numbers/preferred_numbers.htm.

“Preferred Number.” 2025. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. August 1. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Preferred_number.

Additional Reading

“E Series of Preferred Numbers.” 2025. Wikipedia. Wikimedia Foundation. April 5. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/E_series_of_preferred_numbers.

N.Ramani, N. “A Brief Introduction to Preferred Numbers.” 2025. Scribd. Scribd. Accessed August 12. https://www.scribd.com/presentation/520148523/02-PreferredNumbers56-NXPowerLite.

Lippman, David. “17.6: Truth Tables: Conditional, Biconditional.” 2022. Mathematics LibreTexts. Libretexts. July 18. https://math.libretexts.org/Bookshelves/Applied_Mathematics/Math_in_Society_(Lippman)/17%3A_Logic/17.06%3A_Section_6-.

“Necessary Conditions and Sufficient Conditions.” 2025. The Concept of Necessary Conditions and Sufficient Conditions. Accessed August 12. https://www.sfu.ca/~swartz/conditions1.htm.

“Preferred Numbers.” 2025. SCRIBD. SCRIBD. Accessed August 12. https://www.scribd.com/document/152550344/Preferred-Numbers.

“Preferred Numbers and Sizes in Engineering.” 2024. CADEM. December 5. https://cadem.com/preferred-numbers-and-sizes-in-engineering/.

Steenbergen, Martien van. 2021. “E Series of Preferred Numbers and Their Colors.” Observable. July 29. https://observablehq.com/@martien/e-series-of-preferred-numbers-and-their-colors.

“Using Benchmark Fractions to Compare Fractions – Alyssa Teaches.” 2021. Alyssa Teaches. January 15, 2021. https://alyssateaches.com/benchmark-fractions/.

Benchmark fractions are common fractions that we compare other fractions to. They are simple fractions that students are familiar with. They’re helpful to use when comparing and ordering fractions that are harder to visualize, like 8/11, because they can help us estimate. For that reason, they’re also useful when teaching students how to estimate sums and differences of fractions. Generally speaking, benchmark fractions are 0, 1/2, and 1. These are the numbers I’ve used with 4th grade students. With 5th graders, I might use 0, 1/4, 1/2, 3/4, and 1.

van der Salm, Simon A.M. “Renard’s Preferred Numbers.” 2004. The Oughtred Society. Journal of the Oughtred Society. vol. 13, No. 1, Spring 2004. https://osgalleries.org/journal/pdf_files/13.1/V13.1P44.pdf.